The Iron Lady: Cinema Under Thactherism

Commentary, CultureIt is ironic that cinema now has an interest in Margaret Thatcher (with the upcoming biopic “The Iron Lady”) when the animosity of Thatcher’s government toward the film industry, and arts in general, led to major financial cuts, and the abolition of laws that supported the cinema industry. Despite this, under Thatcherism, the 80s saw a prolific output of social and independent cinema, result of the divisions, financial hardships, and social class differences of that period.

The triumph of Chariots of Fire at the Oscars in 1981 inaugurated the decade with a huge success for British cinema. Following major productions aimed at international audiences – like Passage to India (1984) or A room with a view (1985) – presented a critique and romantic portrayal of British system in the early 20th century, very different from the real Britain of the 80s, though.

The Eady Levy was an exchange tax that foreign distributors paid the government for screening their films at UK cinemas. It was a small amount of distributors’ income administered by the British Film Fund Agency. It helped to keep the industry financially healthy, reducing the effect of other taxes on film exhibition.

The levy was called a ‘benign tax’ and meant that a percentage of the ticket price was retained by exhibitors –like a tax rebate-, and another percentage proportional to cinema box office takings were put into British productions. The scheme lasted from 1957 until 1985, when it was terminated after pressures from the US government, being it replaced by a combined system of public and private funding.

The abolition and other policies approved during Thatcherism inspired independent film-makers to turn their anger into low budget creations; social realism cinema with anti-Thatcher explicit content that Peter Wollen describes in Friedman’s book British Cinema and Thatcherism as a ‘British New Wave’; provocative and reactionary productions with social and political content as response of British film industry to Thatcher’s policies and values.

Expert in UK film industry Liz Rymer believes this response led to the emergence of a new trend in British film talent: “There was indeed a blossoming of very edgy, independent talent – and this renaissance has occurred at a great many points in the history of the UK film industry-. Creativity can be seen to blossom when the purses strings are pulled tight, when subsidy is withdrawn etc.”

“The bigger 80s films had all been in development (and subsequent production) for many years – they also had finances that were dependent partly on US input; Chariots of Fire‘s budget was almost all made up of Egyptian money and Merchant Ivory had very substantial financing of their own. So it is very hard to categorize them in the same way one would Channel Four’s output for example.”

In My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) a homosexual love story provides the backdrop for the culture clash between the British and Asian community. Frear’s film depicts a society dominated by racism, and class struggle. The language is strong and abusive with constant references to ‘my people’ and ‘your people’. Within the Asian community, the owner of a car wash business says to an employee: ‘You’ll be with your own people, not in the dole queue and Mrs Thatcher will be happy with me.’ Also, in a father-son conversation, the father says: ‘Think of yourself as a little Britisher.’

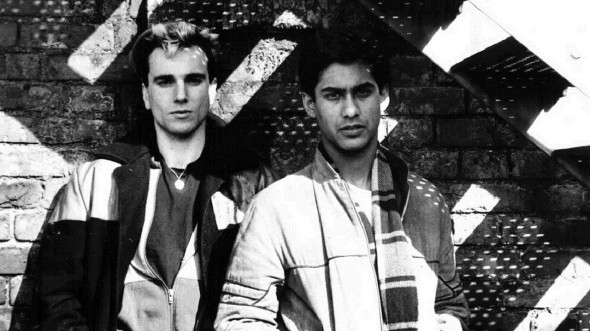

Daniel Day Lewis and Saeed Jaffrey – My Beautiful Laundrette

High Hopes (1988) is a satire of the materialism of Thatcherite Britain through the actions and interactions of his main characters – three London’s couples from different social backgrounds, and the aging mother of the film’s main character -. Mike Leigh’s film evokes class tensions, and social issues like abortion and unemployment, making a more human and intimate portrait of those characters less representative of Thatcherite values. ‘If you ain’t got money. Excuse me for breathing’, says a working-class girl frustrated by her financial hardships to the couple leading characters, who own a cactus named ‘Thatcher’. Peter Greenaway’s surrealist film The Thief, The Cook, His Wife, and Her Lover (1989) depicts Thatcher’s England as a profit-obsessed society dominated by greed, vanity, and social injustice. The only villain in the film is portrayed as the rich, arrogant, and violent owner of a restaurant.

All these 80s productions depict Thatcher’s England as a country driven by avarice and lack of compassion. The relationship between ideology and cultural output was direct during Thatcherism. Now the government has announced funding cuts for arts, so film-makers might face a similar scenario as in the 80s. The question is whether there will be a similar response from film-makers or as the industry declines the inspiration and creativity go away.

Liz says: “I absolutely believe that creative talent will prevail. It has been the case over the last 100 years – the industry declines…the independent spirit come to the fore. It may be more difficult in that ‘real money’ is very hard to come by – but that said, digital kit of sufficient quality is available, this was not the case back in the 80s – so in essence it should be much easier. One always has to take into account the audiences however – they are also much more sophisticated these days. A good example of a film made for next to nothing is Monsters.”

Cinema is a reflection of its time, and these times of financial hardship are bad for film industry. It might be too much to ask for a new British cinema renaissance but, at least, let’s hope the emergence of British film talent for next years.

[…] Story published in Zouch Magazine. […]