The Evolution of the Telephone: WhatsApp, and Speaking in Stickers

Culture, Digital

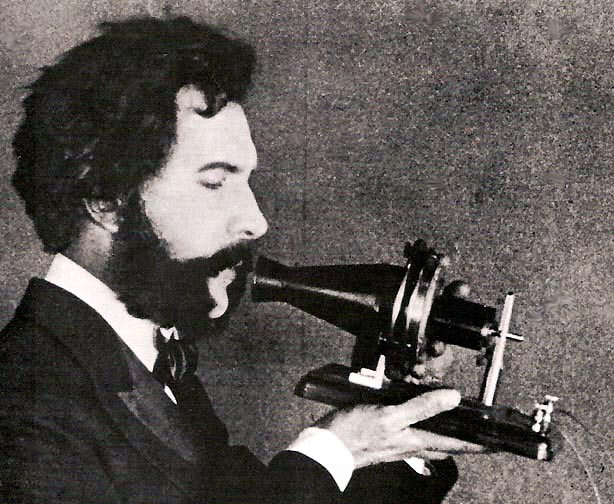

Actor portraying Alexander Graham Bell in an AT&T promotional film

“Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you!” This was the first sentence, spoken over an electric telephone, uttered by Alexander Graham Bell after he spilled battery acid on his clothes. It was the night of March 10, 1876. Thomas Watson was his young assistant.

Ever since, “the story of the telephone [has been] the story of change, of the relentless search for new methods and materials to transmit the human voice,” as noted in a pamphlet produced by the now-defunct Western Electric, supplier to Bell telephones.

On December 3, 1992, a software engineer named Neil Papworth, employed by a British telecom subcontractor, was working on a project farmed out by the European cell phone carrier, Vodafone. He was trying to use the telephone to convey a note. He sent a simple, two-word greeting to one of its directors, Richard Jarvis, who at the time, was at a holiday party. It read: “Merry Christmas.”

It beeped on his Orbitel 901, a portable phone that weighed almost as much as a five-pound dumbbell and had the dimensions of a hardbound book—eight-inches by six-inches by two-inches.

It beeped on his Orbitel 901, a portable phone that weighed almost as much as a five-pound dumbbell and had the dimensions of a hardbound book—eight-inches by six-inches by two-inches.

It was the first text message. As the handsets of the day weren’t equipped with keyboards, it had to be typed on a PC. You could only receive messages, not send them. Nokia added the messaging feature in the next year.

Bell’s invention began to handle telegrams, of sorts. At the time, no one reckoned that the technology would prove epochal.

As time went by, the popularity of text messaging rose to stratospheric heights. People began to love talking more with their fingers than with their tongues. They spoke in “txtspk,” a new language, with a vowel outage.

After roughly two decades of a wildly successful run, there appeared a speed bump in the road. For the first time in a very long time, the volley of text exchanges took a dip. Toward the close of 2012, The New York Times reported, cell phone users sent an average of 678 texts a month, down from 696 texts, during the corresponding period the previous year.

It was a slight decline, but big changes often begin in a small way. The glory days of the SMS (Short Message Service) were behind it and a new dawn was breaking on yet another new mode of communication: instant messaging.

It was a slight decline, but big changes often begin in a small way. The glory days of the SMS (Short Message Service) were behind it and a new dawn was breaking on yet another new mode of communication: instant messaging.

As droves of consumers upgraded to the smartphone—which is, in essence, a Moleskin notebook-size computer, with a full QWERTY keyboard and Wi-Fi—slim, shiny rectangular portals to the paradise of nifty pieces of software calls apps. Suddenly, you had, in your palm, an array of digital serfs.

One such family of workers brought instant messaging to your phone, a convenience hitherto available only on your desktop. Their shining allure was that they were largely free. With texts, customers on an à la carte plan were paying 20 cents a pop (even though the cost of transmitting it to carriers was about 0.03 cents.)

WhatsApp, the more popular of these—made all the more famous when Facebook bought it for a tidy sum of $16 billion, earlier this year—widens your horizon of connectivity. You can talk to anyone, anywhere, as long as they are members of the service—available on devices running on iOS, Android, Windows, Nokia, and the BlackBerry.

WhatsApp, the more popular of these—made all the more famous when Facebook bought it for a tidy sum of $16 billion, earlier this year—widens your horizon of connectivity. You can talk to anyone, anywhere, as long as they are members of the service—available on devices running on iOS, Android, Windows, Nokia, and the BlackBerry.

Like traditional texting, it’s tied to a phone number and when you sign up, scans your contacts to see if their numbers are subscribed.

It doesn’t gag expressions at the 160 character limit imposed by texting, and it displays the conversational thread in the order in which it was conducted. Each message is time-stamped and color coded to distinguish, at a glance, what you wrote and what your interlocutor replied. Inserting photos, videos, or links is easy. To perk up the ambience, roll down a wallpaper.

If you don’t hear back from someone within 12 hours after you’ve sent them a text, and if your beloved recipient tells you that they didn’t get it, there isn’t any way to verify if they’re trying to brush you off, or if your note genuinely bounced off the antennas. WhatsApp ensures that you know what happened. When your accusation has been delivered and read, a check mark appears.

It also lets the user hoist a “status” flag that lets others know if you’re busy or in the mood for a chit-chat. If you’re feeling oddly bitchy and want to rat out a frenemy, you can e-mail the conversation in its entirety.

Its relation to the old SMS was that of the black-and-white sets to the color TV. More control. More reach. More oomph. What’s not to like? Only that it’s free for the first year and costs $0.99 a year after that, over and above what you pay for data usage.

Kik is a service, geared more toward young and the young at heart. It’s everything that WhatsApp is, with a bonus: a built-in browser that lets you surf and come back and prattle on about your finding. This app identifies you with a user name, not a phone number. It caters to the half-bitten apple, the green bot, and the four-pane window.

Viber is perhaps the most versatile of them all and touts it by having a logo the shade of an eggplant. Its peers, for some unfathomable reason, are represented by emblems, the color of a granny smith apple. Its draw is that it has a desktop version and is compatible with many mobile operating systems, including the lesser-known Bada.

Another extra is it lets you place Skype-style voice calls that don’t eat into your phone minutes (though it does chomp on your data if you’re not on a Wi-Fi network.) If you’re fond of speaking in stickers, then, this is your go-to app. It offers more than 1,000 of these, free. If you’d still like to enlarge your vocabulary, you can get more through an in-app purchase.

We use our telephones—“tele,” denoting distance + “phone,” denoting sound—less and less for the purpose they were built for—to carry our voices across distance. Yet, we made them that. A telephone, I suppose, will always be a telephone.