The Evolution of the Water Spa: History

Culture, Design, Nostalgia, StyleIn our culture, the word spa has become synonymous with pampering and reward; from manicures to massages, people tend to view the spa as a treat, an expensive pastime often saved for special occasions like anniversaries or birthdays.

However, our modern interpretation has much altered the foundations of spa tradition. The original meaning for the word spa developed hundreds of years ago in Spa, Belgium, where locals capitalized on the healing power of a hot spring discovered there. Throughout the rule of the Roman Empire, baths or thermae where people gathered to bathe in hot waters, were a popular attraction for all social classes. Today, there continue to be spas dedicated to hydrotherapy across North America, Europe and much of the world, and if you’ve never tried one, you might be surprised by the results.

Aquae Sulis (an alternative name for the town of Bath, England) is an excellent place to start looking at the history of the spa, because much of it is still intact. Despite the concrete evidence to the contrary, there is a long-standing myth about the foundation of Bath, fuelled by Geoffrey of Monmouth’s imagination. He wrote that the legendary King Bladud (father of the much more famous King Leir or Lear) discovered the curative properties of a spring after his pigs had bathed in the mud surrounding it and were rid of a stubborn skin disease.[1]

Yet, Bath was truly established by the Romans in the 1st century A.D. when they uncovered the natural spring source located there and built a sacred site to worship the deity Minerva. At the spring’s source people gave offerings to the goddess Sulis Minerva.[2] Some hoped for retribution or justice, such as the person who threw a curse tablet in the water, asking Minerva to recover six stolen silver coins.[3]

The spring, which produced one million litres of water per day and was a piping 48 degrees Celsius, was engineered to feed the baths. The village of Bath became known throughout the Roman Empire as the place to seek cures for all ailments, including leprosy and rheumatism. [4] Medical experts at the time believed that continual bathing in the waters, both hot and cold, and ingesting the mineral water itself, in small but frequent doses, would have positive effects on the human body. The sulphurous taste of the water would have been an unpleasant remedy, but the popularity of the spa means that it must have been effective to some extent.

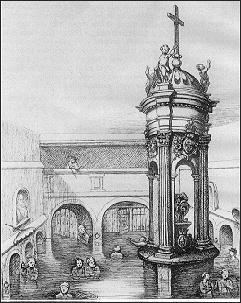

By the 7th century, the Anglo Saxons controlled much of the area, and there are accounts of people using the baths for their curative properties until the 16th century, despite the baths having gone into disrepair several times. Over the centuries, the building around the spring became more and more elaborate, especially since the spa became a destination for the well-to-do and royalty of Britain after the 12th century. By the 17th century, the baths had become primarily about entertainment rather than healing, as musicians, and men with wandering eyes, were stationed on the gallery overlooking the pools.[5] Today, the gallery has been rebuilt and a museum with ancient artifacts from the site have been added for tourists and historians alike to enjoy.

To learn more about modern-day hydrotherapy, come back next week and check out “The Evolution of the Healing Spa: The Modern Day”

“Bladud.” Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia. 20 October 2010. Web. 29 November 2010.

“Medieval Bathing in Bath – History of Bath.” Welcome to Bath. Web Link UK. 1996. Web. 29 November 2010.

Manco, Jean. “Aquae Sulis to Aquaemann.” Bath Past. N.p. 5 December 2004. Web. 29 November 2010.

Trueman, Chris. “Roman Baths.” History Learning Site UK. N.p. 2000-2010. Web. 3 December 2010.

Manco, Jean. “Aquae Sulis to Aquaemann.” Bath Past. N.p. 5 December 2004. Web. 29 November 2010.