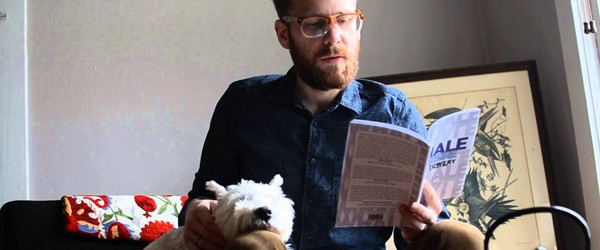

National Poetry Month: {Interview} with Micah Towery, Author of ‘Whale of Desire’

Interviews, Literature, Poetry, WritersMicah Towery’s debut book of poetry, Whale of Desire provides readers—casual readers and intense lovers of poetry alike—with an occasion to think about the way the mind comes to understanding, and love, while navigating self-pity, illusion, and desire. Filled with surrealism that consistently moves from the macro to the microcosm, lofty to local, Towery’s Whale of Desire is by turns funny and gritty, angry and generous. In this Zouch exclusive for National Poetry Month, Towery talks to Shazia Hafiz Ramji about randomness, Christianity, Alfred Corn, and more.

ZOUCH: Whale of Desire has an expansive scope. A lot of thought has definitely been given to this collection of poems. For how long had you been working on it?

MICAH: Some of that expansiveness is because of diverse interests, but Whale also samples almost a decade of my writing life. One poem goes all the way back to my freshman year of college; others were written after several years of marriage. I’m not sure whether that expansiveness is essential to the book or a defect, but as I put the manuscript together, I felt led to embrace expansiveness as a virtue.

ZOUCH: Tell us a bit about the title. Why Whale of Desire?

MICAH: I misremembered a line from the book’s first poem! “Lashed to a green whale, desiring….” When I wrote that poem, I was thinking of the scene from the Moby-Dick movie—the one with Gregory Peck as Ahab—where dead Ahab is lashed to the white whale. As the whale rolls, Ahab’s arm flaps back and forth, beckoning the living to follow him. That scene is not in Melville’s book. It was invented by Bradbury, who wrote the script for the film. Some of my college friends had a band called “The Hungry Ghosts,” and I guess I’m after a similar concept: an almost physical hunger that is so large it transcends our lives and bodies. I also felt that “whale” gestured toward the book’s expansiveness.

ZOUCH: What role does randomness play in a) your poetry b) your life?

MICAH: I’ve never thought much about the concept of randomness in my own life until recently—mostly because Nassim Taleb’s Antifragile inspired a current writing project. I’ve also been reading Peter Bernstein’s history of risk, Against the Gods, particularly as it pertains to economics and market theory. Some of this is research for those writing projects, but I’m also interested in a lot of topics. My wife has learned to just laugh rather than get worried when I come home from the library with 10-15 books on hedge funds or Jean Vanier or whatever is striking my fancy.

That said, randomness is not a conscious thing with my poetry. My writing is like my reading: I follow the nose of my interests. I see myself more as highly associative. I learned some of that from Frank O’Hara, but unlike a lot of O’Hara acolytes, I don’t believe in randomness and inconsequence as an aesthetic ideal. I do believe in happy accidents and fat tails, though.

ZOUCH: It is brave of you to write poetry that is influenced by Christianity, or religion, broadly speaking, especially when it’s not the most fashionable thing to do. What was the thought process and/or the feelings behind intertwining religious elements in poetry?

MICAH: Christianity is my tradition, what’s been handed on to me. In that sense, it’s like poetry. I see traditions as the building blocks of our inner universe. Like language, we receive it from others, but it becomes incontrovertibly personal.

Both poetry and Christianity help me express and examine those structures at the crossroads of interiority and community. In my opinion, though, the best traditions also create the space for critical reflections about those very traditions. That’s the difference between tradition, which is enlivened as it unfolds in unpredictable ways, and authoritarianism, which crushes everything that doesn’t fit rigid standards.

I think that even people who would consider themselves areligious would find deeply felt religious poetry to speak to them also—if only because it’s the collector of so much human experience. As Larkin famously stated about the old churches of Europe:

Philip Larkin

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognized, and robed as destinies.

And that much never can be obsolete,

Since someone will forever be surprising

A hunger in himself to be more serious,

And gravitating with it to this ground,

Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in,

If only that so many dead lie round.

Larkin and I might differ in our belief in objects of faith, but we’re united in recognizing that religion and belief hold meaningful truths about what it means to be human. We ignore religion and tradition at our own peril.

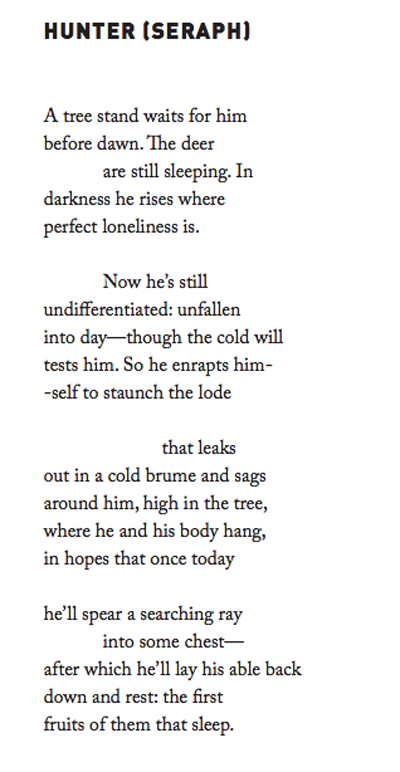

ZOUCH: The poem “Hunter (Seraph)” stood out for me from the rest of the collection. The diction of the poem is refreshing (I’d never heard of the words “lode,” or “brume.”) When did you write this poem? What was it inspired by? It is deliciously haunting.

MICAH: Poets can be tempted by the thesaurus, but at the end of the day we have to find words that seem true and vital for the moment. Those words, along with a few others from the collection (like “ecru” from the “Psalm 39 (Moth)”), are ones that I wrestled with. I’ll admit that these words came in at later drafts after searching for the right term and being unable to find it. I still wonder when I read these poems whether those words are really right. I’ve heard it said that “movies are never released; you just run out of time.” I find that kind of true with poems. You eventually have to step back and say, I’m not sure if this is right, but I’m committing to it until I know otherwise. I guess nothing would stop me from going back and editing those poems later. Why do we have to believe a poem is finished?

I might have felt comfortable going with such a strange diction in that poem because it’s an atmospheric work, primarily. Still, it comes from a place I know well: it’s based on the experiences of my father-in-law and several other hunters I am good friends with. I wanted to take a hyper-spiritualized view of what they did: kind of explode every action with meaning.

ZOUCH: Did you have an ideal reader in mind when writing these poems? When compiling the book?

MICAH: I really want my poetry to be accessible and enjoyable for all. A car mechanic bought a copy of my book because he liked the poem about the junk yard. That was a high compliment for me because it means I tapped into something that resonated with his experience. I have also gotten many positive responses to the book from others, but everyone responds to different poems. I take that also as a compliment because it tells me I’ve tapped into a diverse set of experiences. I see that as positive because I value personalism, both ethically and aesthetically: I want to say with Terence that “I consider nothing that is human alien to me.”

ZOUCH: Is Cat in the Sun Press run by you? How did it come about?

MICAH: Joe Weil and Emily Vogel run the press. Joe was a professor of mine from Binghamton University. Joe helped start Monk Books, and has been seeding small presses, magazines, and poetry scenes for many years in the New York/New Jersey area. He and his wife Emily, who is a professor at Oneonta, wanted to start a new press. It’s one offspring of their artistic union, I think. Like most poetry presses, it’s a small operation with big ambitions. Next on the docket is a book of art and poems from Maria Mazziotti Gillan, and there are several other books planned. Because of the way that Joe and Emily run things, it’s more like a community. There isn’t that veneer of editorial power and control, which is refreshing. As far as I’m concerned, Joe is one of the foremost critics of power structures in American poetry. He writes more potently and perceptively than anyone I know about the absurdities of gatekeepers and the arts. In that sense, Cat in the Sun is an expression of that vision, but because it is tempered by the love and creativity Joe and Emily share, it’s productive rather than destructive.

ZOUCH: You help run THEthe Poetry. Tell us a bit about THEthe Poetry, and how your involvement there contributed to Whale of Desire, in any way.

MICAH: Joe and Emily, my publishers, are directly involved with THEthe as bloggers. But the poetry world is small, so it’s not a surprise that you might work on multiple projects with the same people. But I would certainly love to say that both Cat in the Sun and THEthe are animated by the same spirit of anarchism and open-heartedness. Joe also created an umbrella organization called “Redux Consortium,” which brings together several small presses and outfits. In the future, it’s possible that THEthe might engage in some collaborative work under that umbrella.

ZOUCH: Alfred Corn wrote an introduction. Tell us a bit about Alfred Corn.

Alfred Corn

MICAH: I’m glad you ended with a question about Alfred. When I think of Alfred, I not only think of a good friend, but the kind of glue that holds the contemporary poetry world together. I often picture Alfred as a kind of ambassador for poets, not only because of his own impressive career as a poet, novelist, dramatist, but also because of his expansive knowledge and experience as a writer among writers. One really important thing Alfred does is highlight the work of younger writers and graft them into that poetic tradition of which he is a part. I’ve benefited from this not only because Alfred wrote a generous introduction for my own book, but also because through Alfred I have encountered the writing of other young poets like Jorge Rodriguez-Miralles and Christopher Phelps.