Interview with Matt Margo

Interviews, WritersSometimes a simple Q&A goes in a wrong direction and turns into something bigger than it was to be. You end up having a kind of boxing match with an interviewee – wandering around an imaginary landscape made of the talk. And then you find out that you were hanging in the air all the time and there’s no actual ground anywhere around. And also – there’s no feeling of falling. You just hang there and all you can do is smell yourself. It’s fascinating and horrifying at the same time.

My talk with Matt was meant to be a simple representation of an author and their views on various subjects. But you know – everyone can do that – it’s boring. So it evolved into something bigger. Something else. While preparing it for a publication I found out that it is more of a defamiliarization of a person by their words than any kind of righteous self-presentation. And I must be proud that it turned that way. In some way – what you will be reading in a moment is a fictional conversation based on a fact. It takes place in an alternative reality where time moves erratically mostly by whims. But it’s all true!

So – Matt Margo is a writer who prefers to take a step aside and make some verbal dance moves. You probably read some of their stuff here and there. And you get the idea. Let’s move on.

A long time ago.

Volodymyr Bilyk: Isn’t that funny – to talk about such an intimate thing as writing? “Dancing about architecture” – quote brought an idea that it’s more like talking about something that is not exactly a thing but it is but you can’t actually dig it that way. What do you think about it?

Matt Margo: I agree that there seems to be something about writing (or really, any form of artistic expression) that can’t quite be grasped whenever we talk about it. The essence of the art can be contained only within the art itself, and to talk about the art is to respond to it or run it through some sort of filter, but not to get at its essence or experience it fully. I think that in order for us to truly capture the essence of literature, we must engage with it directly, either by reading it or by writing it. Talking about it contains its own essence that is entirely different and less uplifting, in my opinion. I always feel very nervous and self-conscious whenever I talk about writing, especially my own. It certainly is an intimate thing!

Several days later.

VB: What do you think about the overall practice of giving an interview? Is it important for you? What do you want to achieve by it? Is there a need to express your ideas? Or you just want to construct another kind of conversation – a trickier one – which would be considered as a standalone piece of art?

MM: Well, I am certainly thankful for being offered the opportunity to give this interview, but I want to make it clear to anyone reading that I am generally not the type of person who seeks to be interviewed (unless the interview is a job interview). With regard to my writing, I prefer to allow the writing to speak for itself, as clichéd as that may sound. By writing another poem or having another book published, I have already satisfied a certain need to express my ideas. There is also, of course, social media. I can express any idea that I may want to express or construct any conversation that I may want to construct via Facebook, where there is at least the mirage of some sort of guaranteed readership. Writing and publishing otherwise requires more of a concrete effort to obtain readership. I have often thought about mediating my writing career entirely through social media, though I’m sure that social media must have its own impermanency, its own expiration date, just the same as any other medium. As for the notion of an interview or a Facebook post being considered a standalone piece of art – absolutely! Facebook is literally a book with more than one billion collaborators. And as you interview me now, we are coauthors.

VB: And such ways are transforming for the writer. For me – social media and interviews provide extra material – a line or two or skeletal situation or just another observation to be included somewhere – I think of it as a kind of mine – you can get something or something will fall on your head or nothing will happen at all. What do you think about it? Have you ever experienced something like that?

MM: Yes, that sort of experience is very common in my life as a writer. I enjoy appropriating and recontextualizing various sources of text as various means to various ends. The internet does feel very much like a mine containing literary gems that are just waiting to be discovered. A few years ago, I watched a video of Steve Roggenbuck and Michael Hessel-Mial, two prominent contemporary flarf poets, discussing the concept of “Xanga mining,” or searching through miscellaneous abandoned profiles on the early social media site Xanga in hopes of finding new textual material. That kind of process is something that excites me. So yes, I agree that social media can provide extra literary material, as can interviews.

VB: And this may lead to an assumption that this interview itself is a glimpse to a some kind of parallel reality tailor-made for this interview. It’s not you who answers but a person you built (kinda) inside yourself to answer those questions. And that’s somehow funny. What do you think about it?

MM: I am not entirely sure, but it seems to me that every person is an amalgamation of different selves that result from different contexts and different experiences. My “writerly self,” the particular subject of this interview, is just one of my many selves that ultimately make up who I am. Right now, I am wearing the mask of a writer rather than the mask of a coworker or a cousin or a childhood friend. And yes, in a way, it does seem like each of my different selves lives in a different reality, one that simultaneously coexists with and is separate from all of the other realities related to my existence.

VB: Since it’s a part of our existence – can you blurb yourself?

MM: Blurb myself as a writer? The idea distresses me, but I can give it a shot. “Matt Margo is a person who resides in Ohio and writes poems that are normally about nothing but sometimes about something.” How is that? Blurbing myself feels like writing a personal statement. I had to write a few personal statements while studying creative writing in college, and I never enjoyed writing them. I would much rather let somebody else blurb me or my writing.

VB: How about making it “nothing personal”? I mean – can you make up a character and assume their personality – so you will be able to write about yourself as a fictional character? I think it can lead to some interesting consequences.

MM: I would prefer to leave that task up to someone else who is better at writing fiction. I have written a few semi-autobiographical short stories, but it is typically easier for me to express myself through poetry than to characterize myself through fiction.

LATER…

VB: Can you describe – step by step – your more or less ordinary writing session?

MM: My ordinary writing session has only ever consisted of one step, I think, and that step has always been more of a goal than a step. From 2010 to 2014, when I was studying creative writing as an undergrad, my self-appointed goal was to write every single day, no matter what my circumstances were or how much writing I would actually accomplish, even if I wrote just one line of a poem or one sentence of a story in a Microsoft Word document and then deleted it.

Most days, I’d sit down in front of my computer and write, but some days, I had to use the “memo” function on my cell phone or a pen and a sheet or paper or some other means. But regardless, I couldn’t allow myself to go one day without writing anything, and I promised myself that I wouldn’t. After I graduated from college, I did a decent job of keeping that promise, but as the months passed, I gradually started to break it. Sometimes I would find myself focusing all day on my music or my visual art or my publishing endeavors. So now I’ve revised my self-appointed goal: engage in some creative process every single day. Committing myself to this goal is really the only “step” that seems worth describing. The rest of my ordinary writing session involves simply writing, just the same as any other writer. My ordinary writing session is truly ordinary.

VB: Do you think being ordinary is “bad”?

MM: Being ordinary—as a writer or as a person in general—seems mostly inescapable, but I don’t necessarily perceive it as something bad. Some writing is certainly less ordinary than other writing, and some people are certainly less ordinary than other people, and I typically prefer to engage with that writing and interact with those people, but I think that it is important to remember that there can be an incredible amount of beauty in the ordinary.

VB: What is it like for you to write or try to write every single day? Can you describe the way you organize yourself to do it?

MM: Trying to write every single day is very difficult, which is why I now try to engage in some creative process every single day instead. I have always felt some sort of creative compulsion on a daily basis, and I used to think that that compulsion was the compulsion to write because writing is what I enjoy most, but at a certain point I realized that the compulsion was simpler—it was actually just the compulsion to somehow express myself creatively. On some days, it feels much easier and more liberating to take a break from writing and work on a piece of noise music or a digital abstract painting or whatever else I may want to work on. But no matter how I choose to express myself creatively, there is no real “organization” necessary. I do not need to motivate myself to do it because it’s already what I’m inclined to do. I know that too many people who write like to romanticize the notion of “needing to write,” and I don’t mean to be one of those people, but it is true that I have always been naturally drawn to it, for whatever reason.

VB: Have you ever had an extraordinary writing session? Simply chaotic or in a challenging state of mind or on subversive circumstances? Was it really all that different from usual sessions?

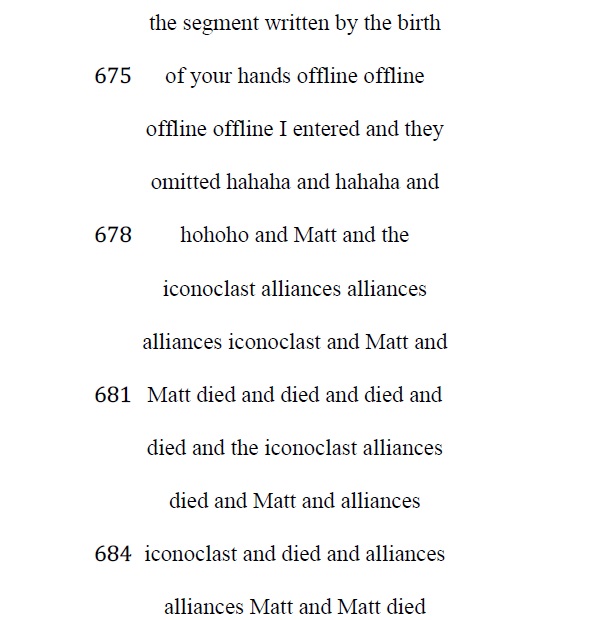

MM: I would say that my most extraordinary or unusual writing sessions occurred while I was working on my book-length poem When Empurpled: An Elegy, which was published by Pteron Press in 2013. Although my opinion may change in the future, I currently view that particular work as my greatest contribution to the world, my best achievement in life. I am not sure if I will ever write a better poem than that poem. And I did indeed write it in a challenging state of mind, under subversive circumstances. To provide a bit of background, the poem begins as a post-flarf mash-up of scavenged YouTube comments translated multiple times from Arabic to English via Google Translate, but it progressively develops into a more conceptualist work that relies on stream-of-consciousness writing more so than found language while also attempting to reflect and/or reinterpret a myriad of influences, including but not limited to (in no particular order): André Breton’s concept of “pure psychic automatism”; Jim Leftwich’s concept of “purely textual asemia”; Nigel Tomm’s concept of “fractal literature”; Zaum; Fluxus; literary maximalism; James Joyce; Gertrude Stein; Hart Crane; R.A. Washington’s book-length poem The System of Mister’s Hell; Lucky’s soliloquy from Waiting for Godot; various religious texts and ancient scriptures; et al. The content/style of the poem is truly chaotic and reflects the chaotic process of writing it. Fueled mostly by manic episodes of depression-induced insomnia and occasionally by illicit substances, I would write for hours upon hours late into the night, always accompanied by a soundtrack of avant-garde jazz musicians such as Sun Ra and Albert Ayler or avant-garde rappers such as Lil B and Riff Raff. My mind was focused on one million different things and, simultaneously, one singular thing, that singular thing being the poem itself. Those writing sessions were definitely unusual, and they definitely felt extraordinary to me.

VB: What do you think about revisions of your own work – finished and unfinished? Is it a vital element of your method? Or you bet on chance? Have you ever experienced a fit of perfectionism that actually destroyed the piece or just made it incomprehensible?

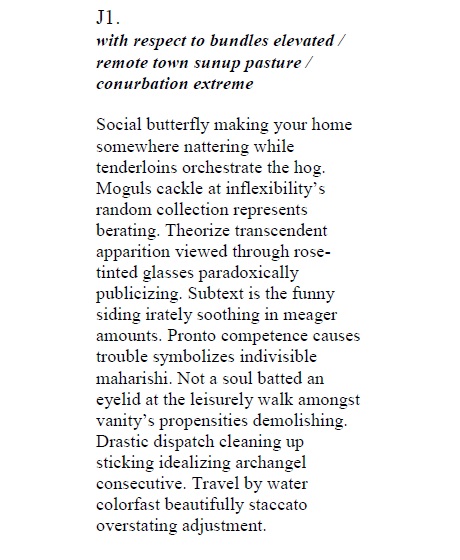

MM: In the case of much of my writing, being incomprehensible is a common goal. Which is not to say that the writing is empty or nonsensical or devoid of meaning. But a sort of incomprehensibility often works well for me as a starting point, depending on what it is that I’m writing or that I want to write. I find that many writers seem to revise their work for the sake of clarity or concision, trying to find a better way to deliver a point or make sure that the reader understands. Oftentimes, however, what seems perfectly understandable to me about my own writing ends up not being understandable at all to most readers, regardless of the clarity of my vision, regardless of my efforts to establish a particular context for a particular text. So I tend to not only assume incomprehensibleness but even embrace it. And that approach usually works for me, even if it doesn’t work for anyone else. But yes, there is still a heavy amount of revision involved in the writing process, normally. I wouldn’t say that it is vital, but I would say that it’s significant. And I greatly enjoy betting on chance as well—both in the sense of not focusing so much on revising and in the sense of incorporating aleatoricism.

VB: What comes after that? I mean – after the full stop. The text is done. You’ve finished the editing – can you describe your usual situation, status after the job’s done?

MM: I usually feel both happy and exhausted when I know that whatever I’ve been writing is finally ready to be submitted, published, or otherwise shared with other people. The general anxiety involved with working on something is temporarily washed away, and I can walk away from my computer and eat a sandwich or take a nap without stressing about the work anymore—at least until it’s time to begin worrying about whether or not anyone will ever read that work.

VB: Have you ever tried to make a piece out of leftover materials? Was it useful?

MM: Normally, I keep any leftovers just in case I may want to return to them but I rarely ever end up returning to them. There is so much new material available that it easy to leave behind the old material and just move on from it.

***

This part was before that part.

VB: Have you ever felt a burnout because of such intense sessions? Have you ever stumbled upon not knowing what to do next?

MM: I burn myself out on writing all of the time. And when I do, I turn to making music, until I burn myself out on making music, and then I turn to another artistic medium, until I burn myself out on that one. I’m always rotating. And I never know what to do next—it seems like something that I should not know.

VB: How about trying to do something across the media – part written text, part music, part images?

MM: I have produced at least one project that fits that sort of description, I think. In December 2012, I took a 3-week college course on experimental forms of writing, and my final project for the course was a post-structuralist series of poems consisting of sound clips from miscellaneous YouTube videos about suicide. I titled the project WHAT SEEMS BLEAK and released it online via Bandcamp as both audio and text.

VB: What do you about reinventing yourself? Have you ever tried to change your writing habits in order to do that?

MM: Maybe not in order to reinvent myself, but definitely in order to try to become a better writer! I feel as if any potential reinvention lies within the writing itself anyway. Each time that I write, I am writing a new extension of myself.

VB: Ever tried to make a collaboration with those extensions? I think it can be a good character piece. Something like Pound’s Personae. What do you think about it?

MM: I think that each new extension of myself is already in some form of collaboration by being informed by past extensions of myself and informing future extensions of myself.

VB: Would you like to construct a whole new and really different persona in order to accomplish some artistic goals?

MM: No, I feel content with just being myself, whoever that may be. A writing persona seems so difficult to craft. The craft of the writing itself is difficult enough for me!

***

Several days earlier but it feels later.

VB: How do you gather raw material for your work? Also – how do you assemble your notes?

MM: I gather raw material for my work from a number of different places. Sometimes I seek out chance operations to dictate the writing process, sometimes I turn to algorithmic language generators online and play with various copy-pasted results, sometimes I plagiarize journalistic and historical resources in hopes of assembling an interesting collage of text, and sometimes I write the way that I assume most people write—I try to find the material within myself and then express it.

As far as notes, I almost never keep notes. While in high school and in college, I was always encouraged by other people to keep a notebook with me at all times and record my observations and ideas so that I’d remember them. But in my experience, most forgotten observations and ideas are not worth trying to remember anyway.

VB: What if there lies something extraordinary and you’re missing that? Or you prefer to taste a mystery of that?

MM: I feel pretty confident that I have not missed anything extraordinary, hehe. The ideas that I forget can remain forgotten without dire consequences.

***

Later that day.

VB: Let’s make a little turn. You have a pretty fascinating publishing activity. Can you tell me more about your history of publishing endeavors? When you have realized that you need to do that? What was the point of entry for you?

MM: I think I realized that I needed to pursue publishing shortly after I realized that writing was not a feasible career option. And I realized that I wanted to pursue publishing shortly after immersing myself into it. Honestly, my publishing endeavors stem more from desire than from necessity. I enjoy the work involved with publishing; it is something that I want more so than something that I need. I am not even sure if I do need it, but it certainly seems more possible to build my resume as a publisher than build my resume as a writer. Again though, any notion of using publishing as a potential means of surviving within capitalism is secondary; what matters more to me is the act itself of managing my publishing endeavors, because it is what I enjoy.

(awkward pause because reasons)

VB: Can you go in detail about your work on Cormac McCarthy’s Dead Typewriter, ex-ex-lit, Zoomoozophone Review, and white sky ebooks? Was it a rocky start? When the groove was caught? When it started to go smoothly? When you started to realize that “the thrill is gone” (white sky and CMDT) and you need to change your ways of doing things (Zoomoozophone)?

MM: My first publishing endeavor was Cormac McCarthy’s Dead Typewriter (CMDT), a blog dedicated to experimental literature, music, film, and art. I created the blog in February 2011, and my initial editorial aim was to put a spotlight on several particular forms of experimental writing that interested me—namely asemic writing, flarf poetry, fiction dribbles, and algorithmic word-chains—as well as to showcase Harsh Noise Wall artists and their music. As the blog began to gain popularity and more people began to submit their work, I gradually became more lenient as an editor and would consider any sort of artistic expression that could be broadly deemed as “experimental.” This allowed me to connect with a wide variety of creative people from around the globe, and by connecting with so many experimental artists, I was able to somewhat establish myself as an editor/publisher within the contemporary experimental scene online.

I had been editing CMDT for two years when experimental poet Peter Ganick suffered a stroke and announced that he would be discontinuing his own publishing endeavor, a blog known as experiential-experimental-literature (ex-ex-lit). I was very much a fan of ex-ex-lit (to the point that CMDT was even partially modeled after it) and did not want to see the blog fade away, so I contacted Peter and offered to take over his position as the editor of ex-ex-lit. Apparently, Peter then conferred with a few of ex-ex-lit’s regular contributors and they all approved of the idea of me becoming the blog’s new editor, so Peter made it happen. At about the same time, I also became the new editor of white sky ebooks, an imprint of Peter’s paperback press known as white sky books.

VB: Tell me more about your time at white sky ebooks.

MM: My time as editor of white sky ebooks was deeply rewarding. When I first took Peter’s editorial position, I felt a wild combination of eagerness and anxiety. I wanted to carry the torch that Peter had lit, but there were of course some feelings of self-doubt. I had a lot of emotional investment in taking over the press. In the summer of 2012, Peter had been kind enough to publish my poetry collection Child of Tree through white sky ebooks, so I was worried that if I failed as the new editor, it would be a professional and personal failure. But fortunately, I managed to succeed! I was able to publish exciting manuscripts of varying lengths from many literary heroes and colleagues of mine (including billy bob beamer, John M. Bennett, and Felino A. Soriano, among others) as well as many experimental writers whose work I hadn’t been familiar with before. Plus, proofreading and formatting all of those publications helped me to greatly improve my editorial skills, which I would apply to later endeavors such as Zoomoozophone Review.

VB: What was it like to publish other people’s work in different places?

MM: Publishing other people’s work through CMDT, ex-ex-lit, and white sky ebooks all at once was indeed thrilling for me, but over the course of the following year, I found myself devoting more and more of my time and effort towards ex-ex-lit and white sky ebooks, while I found CMDT receiving fewer and fewer submissions. In March 2014, after three full years of editing CMDT, I decided to lay the blog to rest so that I could continue to prioritize my other two publishing endeavors, and that decision worked out well for another six months, until I realized how difficult it was for me to manage both a literary blog (essentially a journal) and an independent press while also attempting to be a writer and a college student. In September 2014, I laid white sky ebooks to rest as well, partially because of the reason aforementioned and partially because of a discouraging conflict with a certain well-respected figure in American avant-garde literature (but we don’t need to talk about that). I spent a few more months editing ex-ex-lit only, but during that time I felt a certain desire to establish my own project. I was (and still am) happy as the editor of ex-ex-lit, but I didn’t want to involve myself solely with a publishing endeavor that someone else had started. Also, CMDT, ex-ex-lit, and white sky ebooks were all hosted via Blogger and I was interested in exploring other platforms. Additionally, I did not want my next project to be limited by my usual preference for experimentalism; I wanted to be able to publish more conventional and accessible writing alongside the experimental stuff. I wanted to publish work that was good to me. This, I believe, is the overall intention of all publishers—to publish work that they enjoy. So I eventually settled on the idea of a quarterly online poetry magazine published via Issuu, and Zoomoozophone Review was born.

VB: For me Zoomoozophone feels like an old-school modernist magazine filled with texts that deal with the relatively “unknown” matters. For example – the so-called female issue as a whole can be considered as a certain kind of study of writers as characters represented through their texts. Was it intentional or it just evolved that way?

MM: As an editor, I am always striving to publish more writers who belong to groups that are systemically oppressed. It seems to me that many people perceive the world of poetry as some sort of progressive microcosm that is somehow not plagued by the issues of classism, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, etc. that remain prevalent throughout the rest of society. But I recognize that the work of white men is published and praised more often than the the work of anyone else, and I believe that all writers, editors, and publishers should attempt to do what they can in order to solve the problem of this imbalance. So when curating Zoomoozophone Review Issue 5, which features women and gender-nonconforming poets only (as well as Zoomoozophone Review Issue 7, which features poets of color only), my intention was to offer a bullhorn to poetic voices that are typically marginalized both in the literary world and in the world as a whole. With any issue of the magazine, my intention is to highlight and celebrate those voices.

But I am aware that whenever an editor puts out a call for submissions that is open to any and all writers, a writer who is not white and/or male is most likely going to feel discouraged to submit, precisely because of how white male writers continue to dominate the literary world. A white male writer does not need to worry about his work being rejected because of his basic attributes as a person. In fact, the average white male writer probably has become so used to having his work accepted and published that he feels entitled to acceptance/publication; he expects his work to be accepted and published. Unlike a non-white, non-male writer, he has no reason to submit his work with caution. As an editor/publisher, I want all non-white, non-male poets to know that my magazine actively welcomes their work, and I believe that curating an issue featuring non-male poets only and an issue featuring non-white poets only has helped me to deliver that message to others.

VB: There was also another anthology which you made anonymously – Bravehost Poetry Review. Can you tell about its inception, relatively generous life, and subsequent demise?

MM: I think of Bravehost Poetry Review as the precursor to Zoomoozophone Review—the early draft, the first failed attempt… From approximately 2004 to approximately 2008, the free web-hosting service Bravehost was very popular among me and my friends. We used Bravehost to create personal blogs and terribly unfunny webcomics and “official websites” for local-area pop-punk bands. By now, most of those pages have been obliterated from the digital universe, but Bravehost is still around, even though nobody really uses it anymore, just as nobody really uses Angelfire or Geocities or other similar web-hosting services from years ago. Sometime in 2012, I was thinking nostalgically about Bravehost and came up with the silly idea of using Bravehost to start an online literary journal. But at the time, I was not merely attempting to be ironic. I wanted to prove the point that a literary journal hosted by an outdated internet platform could still be respectable as long as its contents were good enough. Something else that I had never done and wanted to try was edit and publish anonymously, and so I figured that I might as well incorporate that aspect into the experiment that was Bravehost Poetry Review.

Ultimately, the experiment was not successful. Editing a literary journal via Bravehost proved to be extremely difficult because of the web-hosting service’s poor interface and low social status, and attempting to curate and promote the journal through social media with complete anonymity proved to be nearly impossible. I had to resort to soliciting work from friends and colleagues while asking them to keep my editorial position a secret and try to spread the word for me. After several months, I managed to release a decent inaugural issue, and then after several more months, just when I’d almost finished gathering enough work for a second issue, Bravehost locked me out of my account, leaving me completely unable to use their web-hosting service anymore. At that point, I decided to reveal myself as editor, simply combine the contents of the journal’s two issues into one anthology, and release it as an ebook via Issuu. It was probably then that the seeds for Zoomoozophone Review had been planted.

VB: Do you want to repeat such a one-off thing in the future? Maybe as a part of some bigger project?

MM: Honestly, I never know if a particular project of mine is going to end up as an obscure one-off thing or blossom into something more significant. When I was in the process of establishing Zoomoozophone Review, there was a part of me which worried that the magazine would meet the same fate as Bravehost Poetry Review or that it would never manage to launch off the ground at all. Now I marvel at how successful Zoomoozophone Review has been as a publication, and I hope that its success continues to expand from this point on.

***

… months later.

VB: Getting back to more general questions. Is editing for you a balancing act? Some editors trust the authors and their m.o. and some like to assist them to improve their writing. Have you developed your own way of dealing with them? Can you describe it?

MM: Editing is indeed a balancing act, not only in terms of balancing it with my own writing or balancing multiple editorial positions at once but also in terms of balancing any editorial considerations with what an author has presented to me. Generally, I try not to tamper with the stuff that I publish via either ex-ex-lit or Zoomoozophone Review, except for formatting and whatnot. I believe that my task as an editor is to make another person’s work more available while maintaining that person’s original vision and artistic agency as much as possible. I have on rare occasions offered “suggestions for improvement” before publishing certain pieces, but ultimately I invest a great amount of trust into authors with regard to their work. Improvement is always a possibility with any work anyway. I think that most editors who regularly attempt to “improve” the work that they publish are striving for the unobtainable, not to mention projecting a sort of subconscious dissatisfaction with their own work… But assistance does have its place sometimes. Again, it’s a balancing act.

VB: Can you describe the differences between your experiences as a writer and as an editor?

MM: It’s difficult for me to pinpoint the differences between my experiences as a writer and as an editor because editing is oftentimes a blur in addition to being a balancing act. Editing usually tends to feel the same as writing, whether I am editing my own work or another person’s work. Editing and writing are equally enthralling, equally frustrating, and equally rewarding to me. I suppose that I experience a different sort of rush when I’m editing something as opposed to when I’m writing something, but the different types of rushes leave me feeling just as content or just as tired, so any experiential differences ultimately end up not mattering so much. Sort of like everything else.

VB: Since you’re doing it for a long time – what have you learned about writing while doing the editing?

MM: My answer to this question is nothing too flashy or insightful, but I’ve learned a great deal about my own writing via editing other people’s writing. Working as an editor has made it apparent to me that every person who writes is attempting to produce the writing that they want to read. Overall, there does not seem to be many other reasons for anyone to write. We all want to create something that we would enjoy if someone else were to create it, and we all know that it is more fruitful to try to create it ourselves than to just wait for someone else to create it for us. Even the artists who claim to have nothing to say want their nothing to be heard. And paying close editorial attention to the work that other people want to share has helped me to pay closer authorial attention to my own work.

VB: Years ago – in a Banango Lit interview – You went in detail about ‘cutting edge’ – I consider this term to be like ‘film noir’ – something vague and not quite clearly distinguished – as Sydney Pollack once said, “I can tell you I know it when I see it but I don’t know how to define it.” But I also think that being ‘cutting edge’ is the only option for a writer who wants to make a difference. What do you think about it now?

MM: The person being interviewed then is quite different from the person being interviewed now, haha. In that interview, I said that I didn’t think that there was no “cutting edge,” but rather, I thought that experimental writing was the “cutting edge” of literature. Now, I think that there is in fact no “cutting edge,” not even in the form of experimental writing. I still view experimental writing as the most political and most interesting type of writing, but I would not apply the term “cutting edge” to it. It just seems like a term that has no real use or meaning. Plus, I associate “edge” with edginess, and as I grow older I have less and less time for art that is edgy (boring, crass, and socially irresponsible art that attempts to disguise itself as radical and transgressive). And edges are not so important to me anymore anyway. I’m more concerned with the center of things, the heart of the art. I like art that, instead of teetering on an edge, runs from the edge straight into the center and starts a riot there, where there is no safety of climbing over any edges. Years ago, I used to think of writers like Kenneth Goldsmith and Vanessa Place as “cutting edge,” but I know better now. They have the safety of edges to rely on—the safety of white supremacy and the academy. They are not the avant-garde rebels that they swear to be. Alok Vaid-Menon, Bhanu Kapil, Manuel Arturo Abreu, the asemic writing community—these writers are the ones who make a difference in the world and they are not tiptoeing around edges; they are hurtling towards the core of the earth.

***

Quiet a long time has passed since.

VB: Have you ever felt overwhelmed or even fatigued by the immersive amount of various things happening at the same time? This “too much information” exhaustion ever occurred to you?

MM: Yes, especially now in the age of the internet, of course. But that’s not to say that the rise of the internet is to blame for my fatigue or my burning out in response to too much information. Even before I had the internet in my life, I would feel overwhelmed by the heaviness of being, consuming, immersing, learning, etc. I remember one morning when I was about five or six years old—this is probably one of my earliest memories—I was sleeping alone in my parents’ bed and my mom walked into the room and woke me up so that I could get ready for kindergarten, and immediately upon waking up, I thought something like, “What is this? What is this thing called ‘life’? How can I be asleep and things happen to me and those things are ‘a dream,’ but then I wake up and things happen to me and those things are ‘real’?” That was the jist of what I thought. And then I went downstairs and watched Nick Jr. and was a normal kid. But the point is, I’ve always had moments of being overwhelmed. To quote Lil B: “I found out living was a job. Damn, life’s hard.”

VB: Yeah! Living sometimes turns into some kind of foolproof safelock. And that makes a fascinating “what if?” mystery. Ever thought about it that way?

MM: I think “what if?” to myself all of the time. The even more common question that pops up in my mind as I attempt to navigate through this world is “what?”

VB: Have you ever stumbled upon realizing that your lifestyle prevents you from doing something completely left–field?

MM: Well, as a person with a non-binary gender identity, I would like to be able to paint my nails and wear lipstick and physically present myself in a way that is detached from western normative masculinity, but I am currently living in my parents’ house (and in a world that enacts violence against people like me). So does that count?

***

A long time ago but later than previous “a long time ago” but not much + (obligatory Joy Division quote that contains the word “change”)

VB: Can you tell me more about your experiences while studying creative writing?

MM: During another interview in 2013, I was asked a similar question and did not know how to respond, because I was still a student at the time and there seemed to be no appropriate answer that I could give. Pretentiously, I ended up throwing out an excerpt from a David Foster Wallace essay about the flaws of creative writing programs and then following that up with a mostly sincere statement of satisfaction with my own program. I didn’t want to condemn my school, my program, my professors, or my classmates, but I also didn’t want to lie and say that I was happy with all of my experiences studying creative writing. Of course, there were great experiences—experiences that I will always value—but some of my experiences I could have done without. Some aspects of my school and my program were beneficial to my development as a writer and other aspects were detrimental to my development as a writer. Some professors and classmates encouraged me to be myself and other professors and classmates ridiculed me for being myself. I guess that I am answering vaguely because I still do not know how to respond to this sort of question. Like my writing sessions, my experiences while studying creative writing were probably perfectly ordinary. Sometimes I would receive support and sometimes I would be heckled. Half of my writing is an exploration of the avant-garde and half of my writing is an attempt at emotionally transparent expression. I am always either toying with abstractions or crying for help. What young writing student like me wouldn’t have the same mixed bag of positive and negative experiences? I did learn something worthwhile from every one of those experiences though.

VB: What is your opinion on creative writing programs as a process? Don’t you think it’s in some way like sports training? Just instead of calculating movements you’re trained to calculate the form and content. Or is it all about learning tricks and gaining sleight of mind? Am I close?

MM: The comparison to sports training (or sometimes even military training) seems apt. While I was a creative writing student, there were times when I felt like I was a part of a unit like a football team or an army more so than an individual person trying to improve my abilities. Sometimes the insinuation seemed to be that it was more important to follow the professor’s prompt than to produce a worthwhile piece of writing or reach a new milestone as a writer. There was also a certain amount of aggrandizement from time to time—creative writing students were kind of encouraged to feel superior to people who wrote but were not pursuing a degree in it, as though a formal education was the key to validation and success beyond what could be achieved by a writer without the formal education. I say these things not just in relation to my program but in relation to creative writing programs in general. But again, I believe that there is value in being a creative writing student. I honestly do not mean to come off as so bitter and negative.

VB: Much like Mamardashvili once said that there’s no need to look for a philosophy in philosophical studies – because there is no philosophy in there – is it relevant for creative writing?

MM: I think that studying creative writing is a mixed pursuit. There are pros and cons, and if you decide to join a creative writing program, you should expect to experience pros and cons. However you react to those pros and cons is a bit harder to anticipate.

(another pause – for breathing\thinking purposes)

VB: So – can you tell me about one particular experience during your studying?

MM: Would you be more interested in one of the positive experiences or one of the negative experiences?

VB: A positive one – some revelatory experience of sorts or just some weird occurrence? Or you can do both.

MM: I’ll share with you one of the experiences that was both revelatory and weird, with a sort of bittersweet element. Every year at my school, there was a poetry contest open to the entire student body. At some point, the contest started featuring a separate prize awarded to the best “formal poem” that was submitted. One year I submitted a sestina (which is included in my new chapbook Blueberry Lemonade, now available from Bottlecap Press) and won the prize in formal poetry, a check for $50. As an enthusiast of literary experimentation, I have a tendency to turn my nose up at classical forms just as much as I embrace them in hopes of subverting/deconstructing them. Although, there was really nothing subversive about the sestina I’d submitted. I didn’t even write it of my own accord. It was simply an assignment for a class. So it was a bit funny when I was announced as the winner of the prize in formal poetry. Several friends and even one of my writing professors emailed me, saying that they thought the announcement was a joke at first, and I was right there with them, but it did feel elating to receive monetary support for my poetry. The same day that I’d won the prize, I parked my car outside of my dorm, rushed inside for a minute, and came back out to find a $45 parking ticket tucked against my windshield. I could only laugh in response. There was something even more elating about having to forfeit the bulk of my prize money, the beautiful swiftness and immediacy of the loss following the gain. That experience taught me to stray away from placing too much value on capital, both financial and social, and to instead appreciate chance—the absurd, the arbitrary, and the unexpected.

VB: Funny story. Have you ever experienced a catastrophic disaster-like failure that put you on the crossroads artistically?

MM: I have not, although I do believe that my artistic career up to this point has more or less been shaped and reshaped by small, non-catastrophic failures as I have continued to pursue different creative endeavors. These small failures are primarily personal—feeling dissatisfied with whatever I’ve created and deciding not to share it, or sharing whatever I’ve created but then becoming embarrassed by it and regretting its availability to other people, etc. I am in a love/hate relationship with contemporary writers, musicians, and artists having the option to eradicate their work from the internet and thus render it completely inaccessible, because on one hand I think that if an artist chooses to retract or limit accessibility to their work, then that is the artist’s right (as well as an effective way of emphasizing the impermanency of art), but on the other hand I know how it can feel to lose that access to an artist’s work that you love and that has been so significant to you. It is a feeling that can really sting in some ways. Perhaps that is another one of my small failures as an artist—the failure of losing access to some of my artistic influences and not being able to tangibly engage with them anymore. Anyway, the gigantic failures are on their way, I’m sure. At present, I probably have not even reached any true artistic crossroads yet. I’m still young and ambitious, after all. But I do try to engage with art that truly moves me and changes me and forces me to alter my perception of the world, whether that art is someone else’s or my own. To quote Kafka: “If the book we are reading doesn’t shake us awake like a blow to the skull, why bother reading it in the first place?”

***

Godard-jumcut! Million years later a couple of clones are recreating the converrsation with their headphones on.

VB: When did you start to realize the separation between “exploration of the avant-garde” and “attempt at emotionally transparent expression”?

MM: The differences in the approach, format, style, and tone of my writing have always been clear to me, as I think that they are clear to anyone who may have followed my writing for the past few years. In 2011, I was a member of an online self-publishing group known as Let People Poems. One poem that I shared was a picture of a broken plastic fork with the caption “THIS IS A POEM”; another poem that I shared was an alt lit-esque confessional poem about feeling depressed and wanting to kiss somebody. I was publicly mixing aesthetics and it didn’t seem jarring to my peers. They understood that I was involved with different writing circles and had different literary interests and that whatever I wrote was an authentic expression of myself.

My newest chapbook, Blueberry Lemonade, is a collection of accessible, conventional poems about struggling with mental illness and listening to hip hop. My first chapbook, compostable, is a series of portmanteau pwoermds coupled with bits of algorithmically generated mojibake. Both of these works are mine, authored by the same person. I have never felt a need to compartmentalize what I write or limit myself to one particular “literary voice.” I could not imagine only writing conventional poems about my personal life or only writing experimental texts produced with the help of machines.

VB: Can you provide an example of “toying with abstractions” and “crying for help”?

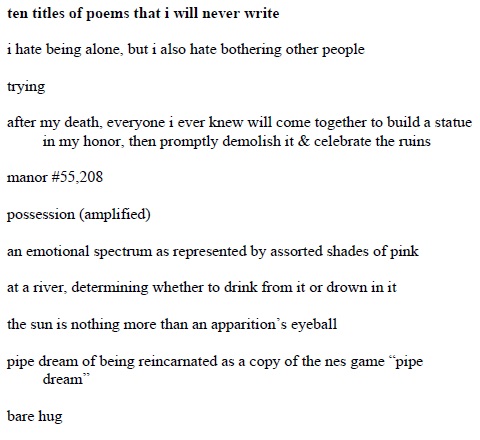

MM: For an example of me “toying with abstractions,” buy my book Two Titles. For an example of me “crying for help,” buy my book Blueberry Lemonade. For an example of me toying with abstractions and crying for help, buy my book When Empurpled: An Elegy.

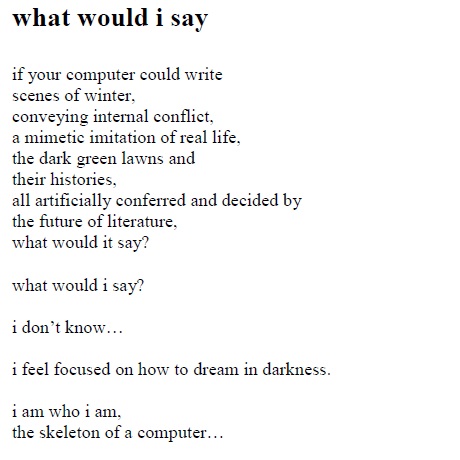

VB: Speaking of machines. What do you think of writing machines? Is it useful for you? In general – do you like to generate randomness?

MM: Simply put, I love writing machines. I love them when they are useful and when they are useless. And simply put, I love to generate randomness. Sometimes the “randomly generated” writing seems more honest and meaningful than the traditional stuff.

VB: What about writing exercises? Is it good for keeping yourself in shape? Or there’s a need to get out of shape in order to do something different?

MM: Writing exercises or writing prompts don’t seem particularly useful to me anymore. I used to benefit from them when I was a student and had to write poems, stories, and essays that were different from what I would normally write on my own, but without the pressure of having to write something and then turn it in as an assignment for a professor, I do not need to worry about “writer’s block” or “keeping myself in shape” or anything like that. The only restrictions or constraints that I consider while writing are self-imposed – a chance operation or an Oulipian pattern that I choose to follow, for example. And yes, I do think it is better to get “out of shape” than to try to stay “in shape.” I prefer the shape-shifting, the transforming.

VB: Can you describe the transformations you passed through in between your first and latest books?

MM: Between my ebook compostable being published by chalk editions in 2010 and my chapbook Blueberry Lemonade being published by Bottlecap Press in 2015, there were several transformations that I underwent – none of which are necessarily distinct by now. But with each passing year, I learned a bit more about being a writer or having work published or promoting that published work. Each new publication helped me to transform a bit more, to keep growing steadily. I wouldn’t have been able to get Blueberry Lemonade published without the knowledge and experience that I gained following the publication of compostable.

VB: Is this kind of reflection in any way useful?

MM: I think so. I do not have the most positive or healthy relationship with myself, so sometimes it can be helpful to remind myself of how I have developed as a writer and what I have accomplished.

***

VB: Is there any ultimate example of “The Thing” which makes you think “Now that’s what I call…!”?

MM: Joan of Arc’s album The Gap makes me think “Now that’s what I call music!” And Joshua Jennifer Espinoza’s book i’m alive / it hurts / i love it makes me think “Now that’s what I call poetry!” But there are plenty of other things that I call music or poetry or both. Everything contains a small amount of both, I think.

***

So this is it. This is the end of an interview. Thank you for reading.