Your Friend Anaya, The President

FictionOf course, you never spoke about politics. Anaya liked to gossip with you, though, about the ranchers and what they were buying and if it would amount to more corn sold than last year. This gave him some anecdotal measure of the countryside, where a rebellion would fester, were one to fester. In the country, nobody but a stranger is nobody’s cousin. So, you never discussed politics with Anaya but your small talk had a point.

You are not the smartest man. This observation does not offend you. When you were a child your father said, “In a world full of idiots you do not want everybody telling you how smart you are.” Anaya loves that little bit of your father’s wisdom. He has used it in several aborted drafts of his memoirs, attributing it to his own father.

In the summer months, when rain falls in the afternoons, you visit the palace and sit with Anaya on his Veranda, overlooking the plaza where the merchants from the mountains sell crafts and coca leaves and spices. In the summer, Anaya serves cava and refrains from smoking. He told you once that the effects of tobacco in the heat started to give him a tightness in his chest a few years ago, so he smokes only when the weather is cool. He has grown fat, you observe. He has not had his uniform altered and it bulges at the belly. Perhaps he believes he is still the large chested hero of the rebellion who had never tasted foie gras shaved over langoustine with crushed walnuts and burnt lemon. Still handsome, yes, but sweating too much and breathing hard. Your friend grows larger and older in front of you. You could have measured him and charted it all, inch by inch, over the course of weekly visits to the palace, starting a few months after the coup. But you say nothing.

You talk mostly about art. When you were children, you both wanted to be painters. You wanted the time alone with your thoughts and then to celebrate your triumphs in white galleries, sharing cups of wine with smart and wealthy people. Anaya thought he would get fucked a lot because the girls back then liked the artist’s way of talking. “I want to paint you, I want to paint you,” he would say and the blouses would fall. The girls all loved Anaya.

For Anaya, the link between art and sex had been forged in, yes, seminal years. So he bought art. He started with the smart pop of Warhol and Rauschenberg but soon attracted a new community of international friends and admirers, people like Christian Laboutin and Chuck Close. Soon, he depleted the treasury on immense, animalistic spectacles like jellified great white sharks in amber by Damien Hirst. From there he went full trash, embracing American tween pop music. Art and sex, art and sex. How does Anaya’s enlarged heart endure? Honestly, the President can mostly just lie there.

Through it all, you got to see Anaya once a week, unless he was out of the country. He spent less and less time out of the country as the world changed around him. One year it’s “welcome to Art Basel,” and the next it’s “we have a cell waiting for you next to Noriega if somebody spots you on line at the California Pizza Kitchen in Miami International. The arrest of Pinochet in 2008 is when the travel slowed and the Arab Spring stopped it. Somewhere in northern California a girl who has devoted the next few years of her life to the study of political science and social economics clicks an online petition demanding that your childhood friend stand trial before the Hague. Thirty years ago, this girl might not have known Anaya’s name but now that she knows that Drake performed for Anaya’s birthday and so she believes that people should boycott Drake’s music. Drake was concerned enough to mention it to Anaya who mentioned it to you. “Hire Ani di Franco,” you told him. “Really mess with their heads.” Anaya considered your proposal but rejected it: “I can go to the mountains for that kind of music.”

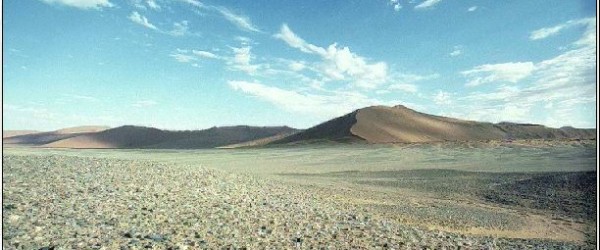

One day on the Veranda, in winter, when they had the heat lamps out and the windscreen and a cold rain fell, drum beating against the tarps overhead, you smoked Gauloises together, like teenagers, and drank mescal out of clay cups, and talked about how your friendship started. It was during the bad days of Mondragon. Your fathers had been assigned to the same air force base at the foothills of the Montequilla Mountains. When Mondragon fell, Anaya’s father had your father imprisoned and tortured for being a leftist. Ironically, when Anaya led the coup against Mondragon two decades later, he would have the man who ordered his father to torture your father imprisoned and tortured as a monarchist. Your fathers lived to their dying days in the same retirement home. They did not talk to each other, but if you asked the other residents, each cared deeply about the other. Your father wanted to know where Anaya’s father was at all times and Anaya’s father never felt comfortable with your father out of his line of vision. They say one could not sleep without knowing that the other was asleep already.

You were both ten when you and Anaya met. He chose you for his soccer team. He chose you last. But you were faster than he expected and defter with your feet. You had multiple steals and passed to him once and he scored. “Who knew back then that you would have your own feed store and that I would become president?” he sipped his mescal. The veranda smelled of mossy rain and peat.

“My mother is sick,” you told him. “She will not stop coughing and says her head hurts.”

“I will send her a doctor,” Anaya promised.

Anaya had the best doctors because they came from Cuba, in exchange for oil in defiance of the U.S. embargo. Cuban doctors are both doctors and field agents. The doctor who treated your mother’s hypertension, glaucoma and Parkinson’s went into the mountains where he encountered a man wounded by shrapnel. He treated the man’s leg, as dictated by the Hippocratic oath and then reported back to the capital. The man, who lost his leg, suffered his injury in the pursuit of seditious activities against his government. We do not know how many would have died had this one man not found himself in such dire need of help.

This is why the doctor tended to your mother in the morning before wandering into the mountains by day, returning home for supper and tending to your mother again, until she went to sleep on her thin bed. Also, he provided flu shots for your children and the treatment for your wife’s anxiety. Also, he was a valuable spy.

When the doctor disembarked on Friday, you went with him to the train station and you went to the capitol together. Dr. Ferrier is a younger man who has seen more of the world and he reminds you of Anaya with whom he shares a confident ease.

On the train, you sit across from Dr. Ferrier. From his leather satchel he reveals a bottle of calvados, a French apple brandy. “Thomas Jefferson loved French wine and French Brandy,” said the doctor. From his bag emerge two glasses. He fills them both half way with amber liquor. You clink glasses with him.

You bring your glass to your lips, take too large a drink and gasp as its alcoholic fumes burn your tonsils. Of course, as this happens, the train hits a bump in the tracks (how could it not?) so that some of the liquid splashes over the rim of the small tumbler and saturates your hand with apple stickiness.

Dr. Ferrier brings cup to his nose and inhales gently as if to perfume his nasal cilia and then he sips the drink and swallows without drama, his eyes brightening as the hot liquid trails into his stomach. Somehow, though you sit nearly knee-to-knee across from one another, his part of the train experiences no bump in the track.

This must have been the moment when you realize that Dr. Ferrier had slept with your daughter, just as Anaya would have, under different circumstances. But these are topics that men do not discuss explicitly because if they did, there could be no peace for anyone. You are, if not mannered, certainly polite. So you ask, “What did you think of the countryside, doctor?”

“You people are a credit to your nation,” says the doctor. “But there are secrets in those mountains. You keep to the town. I am fond of you all. Stay close to home. I am sure Anaya will keep you safe. You and he are good friends?”

You nod. It can be an ordeal to admit that your friend is the most important thing about you. You do not know whether or not Anaya supports your business. Do you have government-backed buyers? Does Anaya tell people to buy their feed from you? Have rivals been thwarted? Have you been protected from threats? All you really know is that you have visited week after week and that aside from the occasional doctor (which is your due as a citizen according to the constitution), you have asked for no favors.

“If I had friends like that, the things I could do,” says Dr. Ferrier.

He pours more calvados. You politely refuse another. You and the doctor part ways at the train station and you shop in the city. You find a Marc Jacobs leather wallet for your wife. Not a knock off. She will be pleased. Then, you go to the palace and find yourself on the veranda.

It is summer, so you drank cava sit in the open air. You listen to revelers below. Anaya wants his people to celebrate something so he sends tanker trucks filled with beer into the plaza and the working men surround them, filling plastic cups from the sudsy teats of the trucks, pushing and shoving and laughing as they enjoy the endless supply. They nip at each other like a litter of nursing puppies.

“You are somber,” you say to Anaya, when he fails to smile at the pop of the cork.

He taps the filter end of a cigarette against the marble table and nodded. He lights his cigarette with a silver torch lighter. Smoke curls around his mustache. He draws his mouth into a line as he lowers the cigarette to the table, where he rests his wrist.

“I wish I could discuss it,” he says.

“But if it would help…” you suggest.

“I never tell you anything and you never ask for anything.”

You wisely change the subject to books. While passing through Anaya’s office you had noticed a copy of Twilight on Anaya’s desk and so you decided to rib him over it.

“It’s a good story,” says Anaya. “I don’t care what people think of me for reading it. Mark my words, in any revolution, the snobs are the first ones who get shot. The factory workers kill the snobs before they kill the factory owners. A factory owner knows how to negotiate for his life. That is a fact. A factory owner begs to live another day. A snob hasn’t finished saying, ‘I wouldn’t deign to give you the satisfaction,’ before his throat is cut and a snob is so stupid that he doesn’t even realize that saying something like that makes it so much more satisfying for the man with the knife. Whatever happens, I hope that I am not a snob.”

“The people love you,” you assure him.

“Some of them even do,” says Anaya.

You stay the night in the capitol and return home the next day by train, excited to give your wife her unexpected gift. You learn on arrival that your store has been ransacked by people from the mountains, strangers to the family.

“Why didn’t you tell me this?” you ask Lucinda.

“I know how much your visits mean to you,” she says.

“I could have asked for help,” he says.

“You would not, though,” she says.

“It is true,” you say. “A shop owner is sometimes robbed. They cannot all go to the President with their troubles.”

You spend the day sweeping broken glass off of the cement floor, righting upturned hay bales and barrels, taking inventory of what was lost. They stole hay but they mostly took food for people like jerky and dried beans and they stole all of the iodine, used for purifying wild water. There are no customers today because the ranchers buy most of their feed and supplies on Monday.

In late afternoon, just as the sun begins to fall behind the mountains, three men pull up in a Jeep. The driver wears mirrored sunglasses and has a bandana tied around his neck. The man next to him is shirtless and wears a bandolier of ammunition. An assault rifle sits on his lap. The man in back is very young, not much older than Trejo. He almost levitates out of the vehicle when it stops and he charges towards you, pointing a finger and asking if you own the place.

“You wrecked my shop?” you say. This would be a good time to tell the boy bandit about who he is messing with and who your friends are, but you are not that kind of man. Friendship is not about favors.

“We need food and supplies,” he says. “For a good cause.”

“You could buy them,” you say.

“We cannot,” he says. “We will need more.”

“How much?” you ask.

“You don’t want trouble, right?” he says.

Of course you do not.

“We can work something out,” you say. “But you deal with me. Only on Sunday mornings, when the shop is closed. No more wrecking my things.”

Really, you think, they did not take so much.

You never learn the name of the young man but you see him once a week and you even become friendly with him. He never again harms your shop. He never threatens you or your family. You never discuss what he is doing in the mountains, who he needs to feed or why, week by week, he seems to collect a scar or burn or two, aging him so much faster than your son ages or than you age, even twenty years his senior.

He is a fan of American baseball. He claims allegiance to the Chicago Cubs who he describes as a plucky, underfunded band of talented athletes who are typically dominated by a moneyed elite. He sees the sport as a moral and economic pageant. He listens to games, he says, over short wave radio. It also keeps his English sharp, he says. Sometimes, when he requests something that is out of stock, like antibiotics for farm animals that you are pretty sure he is injecting into sick people, he will mutter, “swing and a miss.” But he never complains or threatens or demands. What began as a robbery has turned into a civil relationship. You mark this as another triumph of your undemanding personality.

You never mention any of this to Anaya. You could not, of course. To tell your friend the president about this extortion would be the same as asking him to do something about it and you know that he would deal harshly with the perpetrator and that he would deal slowly with him. It is better that your childhood friend and your thief turned friend never cross one another. They could not understand each other. They could only relate through violence.

Then one Sunday, he does not show. You never see him again.

On Friday you go to the Capitol and sit with Anaya. For the first time in months, he smokes and this time it is not just one cigarette. He smokes many, in secession. He smokes to the edge of the filter, stamps it out and lights another. Instead of cava he serves a vintage champagne. He instructs you to savor it. You prefer the brighter cava to this yeastier, more expensive concoction, but you say otherwise. It is a warm and misty night. The plaza is quiet. Anaya has had it cordoned off.

He talks about the new Beyonce album. You do not know what to say about that.

At the end of the meeting he says, “You have never asked me for anything. Your family will be taken care of.”

He hugs you tightly. His sweat has formed a Gauloises cologne. From the veranda, he walks into his office and closes the double doors. You walk down the sweeping staircase into the lobby of the palace and follow the gold leaf lines to the exit. The door is opened for you and you step outside. You are arrested at the top of the steps. A black bag is thrown over your head, your arms are wrenched behind your back, your wrists are cuffed and you double over from a blunt strike (the butt of a rifle, perhaps) to your stomach.

You only had to had to ask for help. Instead, you fed the men in the mountains. How do you think that makes Anaya look? In his unfinished memoir it says that you connected Anaya to real life. It is sadly too late for you to ask for favors. If, however, you want to make a statement? All right, then.

This will be brief.