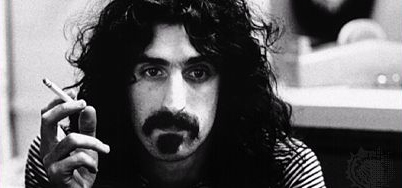

“Frank Zappa” by Scott Marwood

Essays, Music It must have been 1973 or 1974 and I was at York University, not attending studies, but hanging out at the student radio station where I later became the station manager. I had always been fascinated by progressive free form radio. I had my eyes on a job and thought this was the way in. I had received a call one afternoon from an A&R guy at the record label who asked if I wanted to interview Frank Zappa the next day. He was down at the Windsor Arms Hotel and I had to be there the following day, Saturday. Frank was my hero.

It must have been 1973 or 1974 and I was at York University, not attending studies, but hanging out at the student radio station where I later became the station manager. I had always been fascinated by progressive free form radio. I had my eyes on a job and thought this was the way in. I had received a call one afternoon from an A&R guy at the record label who asked if I wanted to interview Frank Zappa the next day. He was down at the Windsor Arms Hotel and I had to be there the following day, Saturday. Frank was my hero.

So I grabbed the only available tape recorder from the station and headed down to meet my idol. Yes, Frank was it as far as I was concerned. Waiting outside his hotel room I felt nervous. The writer for the Sun, Wilder Penfield III came out and said the interview was brutal. Frank said most writers are just auto mechanics, Wilder told us, the remaining journalists waiting nervously outside the room. He also said that Dylan Thomas was just an alcoholic, Wilder added and we all muttered and mumbled in agreement.

Now I was even more nervous as I was next up. I entered the room and introduced myself. There was his son Dweezil and Moon, Frank’s daughter milling about He and his wife were dressed in hotel robes. Frank’s hair was just as greasy as on the cover of some his records. I think he hated shampoo, at least so part of the lyrics of Plastic People goes from the classic Absolutely Free album.

Sit down, he said. There was a body guard standing just behind the couch.

Frank was staying in town, here to do a show in Hamilton, Ontario. I turned on the cassette, which he criticized as being deficient for sound quality. I tested it, one, two three. I told him we used it on news broadcasts and it should be fine. I don’t remember most of the first part of the interview, except I did notice how Frank had started kicking my ankle slowly with his foot, sitting with his leg crossed on his knee beside me on the couch. At first all I noticed was the striped socks and clogs and his hairy legs exposed under his robe. I knew he was doing this to undermine me.

His wife walked past us. Leave the poor kid alone Francis! It was then that I started to dig deep.

The album Trout Mask Replica you produced for Captain Beefheart is said to be a classic. I find that hard to believe, Can you comment? Suddenly Frank stopped kicking me and looked at me as if I had something intelligent to ask.

Yes, he said, the band was drunk and on drugs. I don’t allow drugs in the sessions. So I just put the pots up and left the studio. So whatever they think, it wasn’t really my project.

Frank was warming up. I think he knew that I knew his stuff. Even if I was just twenty-two. I was feeling good here. The nervousness had left me. We talked about the album Lumpy Gravy and I asked him about the influence of Edgard Varese on his work.

Did you know it is the centenary of his birth and that in Buffalo this weekend the University there has a concert to honour his work?

Suddenly Frank had a new respect for me, despite my youth. At that point I signed off and pressing the reverse button,which snapped off immediately at the beginning of the tape, I knew something was wrong.

Frank looked down at it. Was that on?

Sure, I said replaying the first words. Testing one two three…I had a sinking feeling.

Are you sure, asked the bodyguard. I was looking to get out of there fast.

I think Frank knew about the tape.

Okay, it’s all right, he assured me.

On leaving Frank said I could come to his show in Hamilton.

On the way home I scanned through the tape: fast forward, reverse. All I heard was test, test, one, two, three…and the ensuing ubiquitous silence.

Frank is gone and so is the tape that never was, but I have the memory of once talking to a genius.