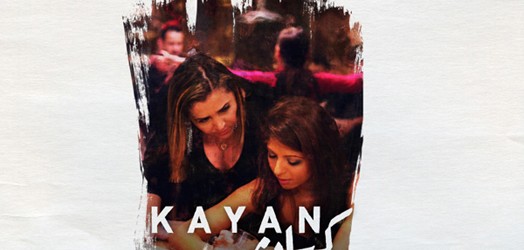

Film Review – Kayan: A Fundamentally Human Story

Film, ReviewsMaryam Najafi’s directorial debut, Kayan, is a film that immerses the viewer in a single environment, effecting a lucid mood. Kayan spans a few nights at a Mediterranean restaurant in Vancouver, following its lead, Hanin, a middle aged Lebanese woman who is the restaurant’s owner. Through her long nights keeping the business afloat, the work at the restaurant wears on her relationships, and her relationships wear on her work at the restaurant. It is clear that it has all come to a point where she is exhausted, and that is only the start.

Najafi’s choice of subject is an important one: Hanin is a single divorcee, with two children, doing her best to run a business. That alone is enough, and yet cultural and personal issues deepen the well. Her relationship with her absent boyfriend frustrates her, she is pregnant, and this is kept secret. A patron, angry about being told to settle his debts says that a woman has no place running a restaurant. Yet, she always does her best to persist because, like many immigrant women and mothers, she has no other choice. Oula Hamadeh (who is the real life owner of Kayan Restaurant in Vancouver, BC) plays the lead role of Hanin with a steady hand throughout as a woman under pressure, but never faltering.

The film’s relationship with its lead is primarily external. Much has to be deduced from observation as Hanin rarely has time to confide in anyone and must keep a strong face through out. It is difficult, at times, to fully know what is at stake for her. However, there is a clearly formed character at the film’s centre. On the peripheries it is less so, since many of the supporting characters seem to revolve only around Hanin: A Persian man who has recently immigrated from Iran takes an interest in her, but his reality is unexplored, aside from a few cursory details such as his piano playing; another woman, who later proves to be important, spends most of her time drinking at the bar, and ignores her son in favour of her drinking. Despite the potential for development, these peripheral stories are left to the imagination. On the surface, the relationships lack ambiguity, depth, and seem to be egocentric. However, they complement the feelings of stasis, frustration, and monotony that Najafi instills at the beginning of the film, and which are important for sustaining the mood.

Kayan is interspersed with many small vignettes. One of the waiters, Neda, tries to slip her struggling colleague an extra fifty dollars as she is leaving. Later on, she helps her clean the wine she’s spilled on herself, calming her and letting her know that she is wanted despite Hanin’s stiff manner. A belly dancer carefully balances a sword on her head, moments after handing her baby to Hanin. These moments are short enough to pierce through understanding, and more is not necessary. They prove to be the film’s greatest strength, and the key to its immersion.

Kayan lacks the refined fluency that helps suspend disbelief, but this is almost a given for debut feature films. Regardless, Kayan is worth watching for its subject matter, for its pursuit of narratives and characters that are often under-represented in culture, and for its warmth as a fundamentally human story that is easy to relate to.