{Fiction} The Cistern Miser

Fiction, LiteratureDad sits across from me, swallowing water between each mouthful of food. He sets the glass and fork down, and his lips begin to move as if he is attempting speech, but he doesn’t make a sound. One of the weird things that has happened to him as he’s gotten older is that he now mutters whenever his mouth is not occupied by food or genuine talk or yawning. I’ve no clue if he’s really trying to say something, all I see is a soft mashing of his lips without any noise or eye-contact. I don’t want to upset him by drawing his attention to it in case he doesn’t realise, so I don’t mention it ever. He could be working things through in his head before he says them, which might be something you have to do if old age starts slowing your thinking, though no one’s told me of any diagnosis like that. Either way, eventually he looks at me and speaks.

“Why’d you choose this one?” He asks with a kind of gruff tone he uses sometimes to remind me of my place. “I don’t know about yours,” he says, lifting up a forkful of stewed vegetable and tilting it until it drops back onto his plate with a splat, “but mine probably isn’t worth the money.”

“Don’t worry about it, Dad. You didn’t pay for it,” I reply, trying my best not to sound like a parent.

****

He explains his broken arm to me, and does a good job of making me sound like the invalid. He fell.

“Stupid, really,” he says, “still can’t work out how I did it,” producing a laugh that feels completely forced, and says to me very clearly that his broken arm is an inconvenience that weighs almost nothing, and that the worst response it can force from him is a bit of a chuckle. Some people chuckle frequently, and any half-heartedness is pretty much just there to show off the times when they laugh freely, but Dad is not one of these people – in fact his sense of humour has shrunk over the years to the point that he now even complains of being bored by The Two Ronnies.

“I’m amazed the doctor who fixed my arm wasn’t Indian,” he says, I think probably trying to provoke me, so I only mutter an ‘uh huh’ and keep my attention on the documentary he wanted to watch about the technological prowess of the Nazis, and what it might have meant for the war if only they’d avoided defeat for another year or two. “Even more amazing, the nurse they had looking after me was a man. Gay I reckon. Disgusting if you ask me, but they had me on painkillers, so I didn’t think to ask for another,” he continues. Again I say nothing, and concentrate even harder on the black and white figure of Werner von Braun, and the possibility that the first man on the moon might have worn a swastika on his spacesuit instead of the stars and stripes. I can hear more of Dad’s wordless mouthing as he notices my silence, which he makes one final attempt to break by trying out the idea that maybe Hitler was ‘on the right track’ in some ways, before he retreats into muttering anger that might actually be directed entirely at himself.

“Turn off those hall lights, it’s like Blackpool illuminations out there,” he says, pointing suddenly towards the open living room door. He stabs at the light-bulb, sweeping his good arm up and down like he’s beating time to the march of money burning away on the incandescent filament. “And close the ruddy door while you’re at it, you’re letting all the heat out.” I don’t mention that the fire is unstoked and the radiators are cool to the touch.

****

“Get your fucking hands off me! Get your fucking fuck hands off me! Fuck f…f…f… fuck off!” The word ‘fuck’ seems like it’s gotten stuck in his mind or on his tongue, and it sounds so weird coming from him that I actually laugh, which he doesn’t like. “Don’t you dare laugh at me you fucking wimp! You fucking wimp! I remember how you used to cry to your mother. Don’t you dare laugh at me in my own fucking home.” He really does stress the word ‘dare’ and I think if his arms weren’t caught up in his undershirt, he’d probably make a fist and threaten me with it.

He eventually frees himself and sits there with a confrontational look straightening the wrinkles out of his forehead, even though his arms are still outstretched waiting for the next stage of his bedtime routine. I don’t know if he realises that he is giving me a performance, if he knows that the silver on his back has faded to the point where it just blends in with the greyness of his skin, and that his pride, which was once like a fist he beat us with, has been sapped to nothing by his incontinence pads and his pitifully recognisable frailness. To me it is obvious – something changed for me months ago when he first fell – without wanting to I began to feel sorry for him him a bit, but also to relish my pity for what it said about who was now dominant between us. He stopped being someone I was in conflict with, and simply became someone I cared for.

I am trying to help him clip his nails. I had noticed earlier that they were becoming long and nasty to look at – not curled like those of a holy man, just the yellowing crud encrusted claws of an old and probably iron-deficient pensioner. What worried me particularly were his toilet habits; his nails seemed much filthier after each (frequent) trip to the loo, and of all the indulgences he can barely afford, poor bathroom hygiene is up there with his taste for panatellas and looking warily at any black male he encounters. As he stretches out his knuckley fingers towards me, I do believe I spy the unmistakable presence of shit beneath the ridged surface of his talons, and wonder for a minute whether this is the kind of job I could reasonably leave to his care worker. The thought of him idly chewing on those same splintery nails during mid-morning repeats of antique shows and business news convinces me that it’s really my duty. Shards of brown and yellow nail squirt off onto my lap while he happily informs me that he could do a neater job even through the clutches of his arthritis.

“Doesn’t it piss you off being my bloody nursemaid?” He asks, finally. “If it doesn’t, it bloody well should. I never did this for my father, he wouldn’t have expected it, not when I’d got my own family. You’ve got your priorities wrong. Your wife’s probably running around with another man while you’re here wiping my arse.”

Some of the glee is gone from his voice as he makes this pronouncement, like there’s a genuine sadness to be felt at the fact that I am brushing his nail clippings off my trousers and into a waste basket instead of fucking my wife. I could tell him that my wife would probably never fuck me again if I left him to rot amongst his local papers, his wedding crockery and the power tools that aren’t safe for him to use. I could tell him that the pleasure of sleeping with my wife, or spending time with my kids would be reduced in some nameless but undeniable way if I knew that he was sitting alone with his broken arm in front of his three-channel tv.

I could even tell him that I hoped that by setting an example, despite the cost in time, anger and resentment, I hoped to make sure that when I am old, my own children will remember and try to do even better by me. And in fact, all of these are true, but none of them actually matter, because I don’t feel like I have a choice. He signals that he’s ready for bed, and settles onto his back before jerkily rolling onto his side, probably to prove he still can. I turn out the light and close the door.

Dad’s room sits right above living room, and I know better than to risk the noise of the television filtering up through the concrete floors. I send a text to Allison, telling her that Dad has gone to bed, and not to call me because he’ll hear the murmur of my voice and thump on the night-stand to signal that I should shut up. I think about making a joke of what he said about her probably fucking someone else while I’m here looking after him, but decide against it as neither my Dad’s ill-health nor her loyalty are the kind of things Allison likes to joke about. I sign off my message with two kisses because Allison has always said that one isn’t enough.

There isn’t very much of Mum left in the house. I don’t blame Dad for this, and remember the few days we spent after her death removing things that were hers, or which reminded him of her. He’d said the only way to move on was to leave things behind, and so we boxed ornaments and books and a small wardrobe’s worth of clothes, and even dismantled their bed, which was replaced by a single with an orthopaedic mattress made from expensive foam. Ten years is a long time dead, and I have fewer memories of Mum than I’d like; she didn’t slowly decline before she died, and so I didn’t make any special effort to remember what made her my mother before a brain hemorrhage took her away in the fresh fruit aisle of Marks and Spencer.

This is probably part of the reason why I am sitting in Dad’s dingy lounge, with nothing to do before I go to bed. His attitude towards Mum after her death is maybe also the reason I haven’t tried harder to remember her, and why between charity shops and Ebay we kept nothing that was hers – it isn’t so much the leaving behind that is important, but more the steps you take to push away from yourself the things you can’t keep with you, but wish to God that you could.

Dad’s bookshelves are pretty bare, with just a few histories of battles during the two World Wars and a novel by a horny Conservative politician, it’s spine almost cracked white to the glue underneath. Allison has always hated Dad’s taste in books and tv, and gives me a look whenever I threaten to buy something she thinks is ‘more your father than you’, like she expects an interest in military history or cricket might be enough to ruin me as a parent. None of his books appeal much to me, so I thumb through the tabloid he gets delivered from the local newsagent. The news is mostly silly and overblown, but the sports section is pretty thorough and wastes twenty minutes or so before I decide to go to bed.

I get my toothbrush from my wash-bag and head for the bathroom. Dad has allowed someone to plug a night-light into one of the sockets along the wall and this creates a silvery pool on the carpet, but it doesn’t leave much of the rest of the hallway visible. This doesn’t matter much, as the journey from my childhood room to the bathroom is imprinted, well-practiced like a punch rehearsed for an after-school fight, even after all this time. I can remember the position of all the old squeaking floorboards, and tread lightly enough that the couple that have sprung up in the years since don’t moan too loudly when I step on them.

It always used to be my mother who’d hear me if I got up in the night. Dad snored like a cross-country train, nine hours from London to Glasgow every night, which probably explained why she was a light sleeper, though it didn’t explain why she got so annoyed at the sound of the floorboards. She’d question everything from my bladder control to my clumsiness the next morning, but he never seemed to have noticed anything and looked on disapprovingly as we bickered, scowling at us for ruining the quiet of his breakfast. I never hear my own kids if they get up in the night, they have a lightness of foot that they don’t get from me, and I think the build quality of our house is better than Dad’s, which was put up in a hurry some time during the 1960s.

My gut has the thickness and heat of a peat bog, and I can feel chili and beer mixing in my stomach like they’re the chemical secret of Nazi rocket fuel. The door swings shut freely, and the lock rings loudly as I shove the bolt home, but to be honest my mind is elsewhere and stays there until the burning sensation in my belly violently disappears. There’s something a bit pathetic about being an adult and shitting like a child, as if the watery filth carries away with it all the control and stature that proves you a man. The smell and the basic unpleasantness lend an unnecessary aggression to my yank on the flush’s silver handle, and it’s with almost childish confusion and despair that I realise that nothing has happened.

Somewhere within the enameled rectangle of the cistern, a muffled clunk thumps with each pump of the lever, but not even a dribble of water emerges to rinse the bowl.

I waggle the handle a few times, uselessly, as if the simple mechanism might actually be complex and temperamental, requiring time and patience. There are many ways in which I feel superior to Dad, or at least more developed, but I have no talent for fixing things. It is only in the last couple of years that Allison has stopped calling him for advice with repairs around the house, and then mostly because his patience has worn thin with age. I twist the cold water tap, and a forceful splash makes a run for it over the lip of the basin before puddling on the vinyl tiles below, so I turn back to the toilet, and approach the heavy lid of the cistern like a tomb robber looking for gold, or curses, or jackal bones.

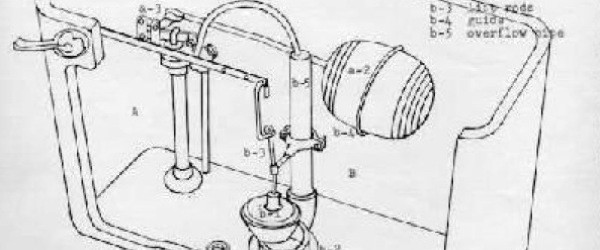

Beneath the porcelain lid sits a network of pipes and valves and floating plastic spheres, all of which I understand in some vague way to belong within the cistern’s lime-scaled insides without having the first clue what they do. However, I do recognise a problem when instead of water sloshing between the plastic tubes I find only bricks. Full house bricks, quarter bricks, shards of brick taking up every last bit of space beneath the flush mechanism. With the lid off, I tug on the lever again a few times, but the bricks have been so carefully placed that they don’t get in the way at all.

A decade or so earlier, during a summer when it was so hot they’d announced hosepipe bans and emptied all the swimming pools, I remembered that the government had asked everyone to place a brick in their toilet cistern to lessen the amount of water needed to flush away the nation’s business. It sounded like the kind of advice Dad would’ve taken notice of, and probably stuck with even after the sun got lost rejoining the yearly merry-go-round of cloud, cold and rain. He liked to economise.

I wonder if I should wake him up, so I can find out immediately whether this insane bricking up of the toilet is the peak of his tight-fistedness or the first scratchings of dementia. There’s no sound of snoring from his room when I open the bathroom door, and there is probably a good chance that he is awake, listening to me, counting squeaks in the floorboards so he can list them in the morning as if each one woke him up separately. Instead I return to the open cistern and begin to remove bricks, stacking them in a neat pile beneath the towel rail. The water level begins to rise, and once it is above the level of the valves, I pull the flush again and almost clap my hands in self-satisfaction as the stinking mess quickly vanishes.

In the morning, I emerge from my room once I can hear Dad clumping about, and make straight for the bathroom, aching for a piss. It doesn’t surprise me when I see the bricks gone from their stack under the towels, nor when I hear the empty clunk of the handle as I reach for the first flush of the day.

[…] published that deals tangentially with water bans and other aqueous obsessions. It’s called ‘The Cistern Miser’, and you can read it at Zouch Magazine. This entry was posted in Uncategorized by philip. […]