It Was Defiance

Fiction, LiteratureWhen I was very poor and could not afford the luxuries displayed on screens, I would become quite sad from time to time.

It was silly, I realized that even then. Most of those flashing promises did not interest me one whit. But there is a grave difference between lacking something simply because you choose to, and lacking something because the choice is not yours.

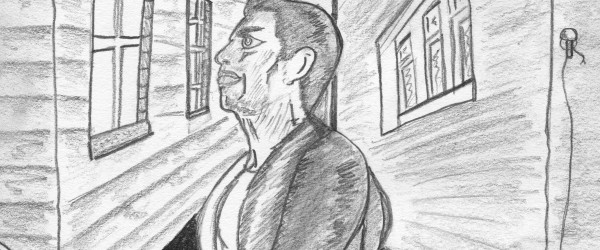

In those sadder moments I would cruise through the warm evening, deliberately slow, down to the health food shop to buy myself a chocolate bar.

Not a slickfake kind of chocolate bar that you find in a gas station or a chain-pharmacy. But something fancy, wrapped in layers of thick paper and real foil, three-dollar-dark chocolate bars. They felt substantial in my hand, the way I imagined it would feel to hold a large stack of crisp new bills or a classy lady’s pocketbook.

The one I liked most had forest mint leaves woven into its creamy soul. It was manufactured by a company that gave ten per cent of its proceeds to a wildlife protection fund. I hoped my ten percent was getting to frogs, and not something irritating like lemurs.

The world back then was wrought with immediate satisfaction. She was wracked with cheap tricks to slake any hunger or create the illusion of any luxury. What was a chocolate bar? To most folks, even poor folks, my occasional indulgence would mean nothing. It was less than run-of-the-mill significance. It was below thought.

But to me, in those quiet moments of sheer poverty, letting the tiniest piece of the tiniest corner of one square of chocolate melt in the crook of my tongue… it was everything. It was beauty and it was restraint. It was promise. It was hope. It was defiance.

I would sit in the quietest chair I could find with a single square of chocolate (two if I missed my girl) and break off minuscule slivers with my two front teeth. The piece would sit on my passive tongue, melting like a traffic cone in the Georgia Summer, slowly but irreversibly. I savoured every molecule.

I placed my golden forest mint chocolate bar in a small wooden box, just like Charlie Bucket. He only got one a year, and would make it last a whole month. Most days I didn’t open the box. I thought about Charlie Bucket’s dad, whose job was to screw the caps onto toothpaste tubes in a factory.

I remembered with sickness how much I was indulged as a child, how much I indulged myself as a young man. I thought about how appreciation as a genuine emotion was dying in the muddy cultural waters of the then-present generation. I thought about discipline and humility. I thought about righteousness and desire. I thought about watery cabbage soup.

And when I was thoughtworn, and my neurons were sparse as a threadbare carpet, I would open my tiny wooden treasure chest again and carefully break off another small square. Gradually, private moment by private moment, the bar would shrink and disappear, until I carefully creased the wrapping paper and folded it into the bin.

But those were the moments that restored me. They gave life to my ailing spirit. And I would give everything back if we could have shared them.