Canadian Loserism

Commentary, Culture, Essays, FilmThe “loser” protagonist has been a trademark of Canadian media for generations, but has been particularly notable in the past decade of mainstream English-language TV and film, with the most obvious examples being the beloved Trailer Park Boys and Terry and Deaner of Fubar, and most recently, Fubar 2. Why, in the post-“I AM” age of renewed Canadian nationalism (at least on the commercial level) is the Loser still such a revered caricature? Is it lazy storytelling or indicative of an ongoing national identity crisis, in which our geographic limitations translate into class signification?

For the purposes of argument, Ricky and Deaner are essentially one in the same. While the Trailer Park Boys are a self-deprecating manifestation of Atlantic hinterland sentiment, the Fubar boys in turn represent redneck Western alienation, each side representing the Loser as defined by specific, “neglected” regions of the country. What Fubar lacks in supporting personalities (Bubbles, Lehey, J-ROC, etc.) it makes up for in crippling realism. However both worlds serve the same purpose: making us laugh at our very Canadian pathetic-ness.

And they do make us laugh. Fubar 2 is crowded with clever wordplay and ludicrous physical humour. Trailer Park Boys, particularly the Showcase series, have been arguably the most important force in Canadian comedy since Mike Myers jumped the shark. Terry and Dean are sympathetic in the same way that Ricky and Julian are: they are so blissfully lost in their ignorance that we are able to look into their world from our own Canadian comfort and root for them. We root for them to make it in spite of their idiocy, and therefore accept their role as the Loser as defined by their class, and in turn, geographic destitution. We root for them because they are part of who we are. And Dumb, when sincere, is funny.

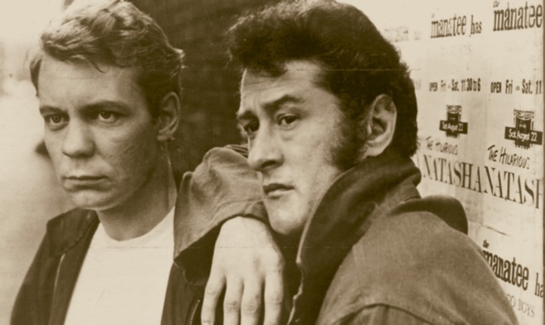

But why is our cinematic identity often so one-dimensional, or better yet, why is it that only the losers seem to have the most lasting impact? From landmark Goin’ Down the Road (1971, pictured above) to Joe Dick to Bob and Doug Mackenzie, we have often found it easier to make art out of our shortcomings than celebrate our achievements. Catchphrases aside, we celebrate the Loser not because we feel like a nation of losers, but because we concede that our national identity is one that constantly strives towards acceptance and recognition. This becomes manifest in Ricky’s quest to finish his grade 10 education, or in Terry and Dean’s journey north to earn big money working on the tar sands of Fort McMurray AB. There is always the just-unattainable goal of “making it,” which is inherent of a little-brother nation such as ours.

Our big brother down south has many famous losers as well, but even taking Kenny Powers (Eastbound and Down) as a test subject reveals much about our differing national identities. Kenny is a disgraced athlete trying to rebuild his life; while he has all the god-given talent needed to achieve stardom (and he once did), his station in life comes only as a result of his debilitating ego and excesses. He is a loser by his own doing, despite opportunity at his fingertips (literally), but he is not inherently disadvantaged. To overcome his personal demons is to be once again on the path to the American Dream of fame and fortune. In Sunnyvale Trailer Park or the skids of Alberta, there is no such opportunity. Ricky and Julian only ever aspire to not work and own a trailer, while Dean’s emasculated existence, underpinned by his white-ghetto upbringing, is made literal by the removing of his testicles, one in each film.

Of course, it can also be reasoned that Canadian character development is restricted by the very film and television industry that makes it so difficult to adequately finance projects. Recent Trailer Park Boys seasons as well as Fubar 2 operate as “cheating” moc-docs, in that they utilize documentary aesthetic (cheap handheld cameras, sharp cuts, interview segments with characters) but also pick up multiple camera angles, include fantasy sequences, flesh out the production and no longer include the documentary-making process as integral to the narrative. Lazy, yes, but also necessary in a system which prevents young filmmakers from getting adequate funding to compete with slick American work. As such, the Loser protagonist is perfectly fit for the low-budget video look that Canadian filmmakers are often forced to employ; the visual aesthetic template has already been laid out by years of COPS episodes. TPB director Mike Clattenburg has gone on record talking about making “the cheap look part of the show.” Would it be realistic that Terry and Deaner’s binge drinking would be captured on a 35mm Panaflex? Of course not.

The Canadian Loser is not our sole onscreen representation, we also have gas station bumpkins and Strombo the rockstar and a really stupid-looking new hockey musical (Score!, which somehow opened TIFF this year..) We are a generally proud, albeit growing nation, still struggling with identity. But as long as Terry and Dean are inspiring shotgun competitions and people line up to see TPB characters get drunk and do stupid things on live stages across the country, we continue to see a piece of ourselves in these characters, for better or worse. As Clattenburg himself puts it, “A lot of people say they know a Ricky.” As such, the nature of the art demands attention from its audience. Fubar and Trailer Park Boys are purporting a stereotype and a reality: the two are bound, which is an important social comment, and one that transcends the Loser to the status of cultural benchmark.

*Mike Clattenburg quotes from: “Trailer Park Boys Return to Their Roots” by Alex Strachan for The Ottawa Citizen, April 16, 2005