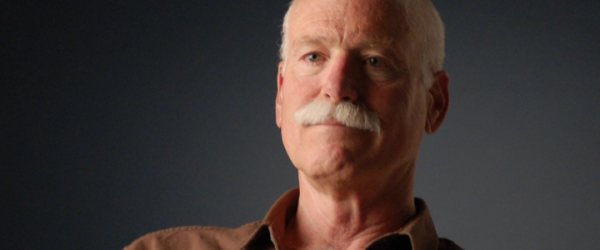

Book Review: “Our Story Begins” by Tobias Wolff

Books, Reviews

I’ve been hearing a lot about Tobias Wolff recently. After studying the Collected Works of Raymond Carver last year, I watched the Criterion Collection edition of Robert Altman’s film “Short Cuts”, a jazz-inspired pastiche of Carver stories set against the paranoid backdrop of early 1990s Los Angeles. In a documentary included on DVD’s bonus features, Wolff weighs in on Carver’s uniquely bleak sensibility, describing with wonder that artist’s attraction to the darker side of the human soul and his methodical process of revision.

Wolff’s work couldn’t be more different from what we think of as Raymond Carver’s (“Leviathan” being a notable exception). I mean this as a compliment – the stories assembled in “Our Story Begins” are told with a patient, steady hand that manages to avoid overly sparse or idiosyncratic tricks of language. Though on the surface these characters are just as doomed and hapless as Carver’s, Wolff manages in many cases to mine some buried vein of hope that pulls the narrative back from the brink of total despair.

Take “Desert Breakdown, 1968”, where a pregnant Krystal is left stranded in a shady desert backwater with her toddler son. Surrounded by threatening locals who may or may not have violence on their minds, Krystal finally realizes about her husband: “Mark was not there. As if she had really believed he would be there. Krystal kicked the wall with her bare foot. The pain made clear what she had been pretending not to know: that he had never really been there and never would be there in any way that mattered.” Inspired by this insight and empowered by her anger, Krystal manages to assert herself and gain the upper hand in what had seemed like a hopeless situation.

This is the kind of emotional epiphany we often want – and fail to receive – from the typical minimalist American short story. While Carver and Williams and other proponents of dirty realism might leave us breathless with despair, sucker-punched in the gut by banality or horror, Wolff allows his characters to move beyond the paralysis imposed by circumstance and move on. This is true even in the face of certain death, as in the wonderful “Bullet in the Brain”. In it, a man’s life flashes before his eyes in the microseconds after being shot in the head:

This is what he remembered. Heat. A baseball field. Yellow grass, the whir of insects, himself leaning against a tree as the boys of the neighborhood gather for a pickup game. He looks on as the others argue the relative genius of Mantle and Mays. They have been worrying this subject all summer, and it has become tedious to Anders: an oppression, like the heat.

Then the last two boys arrive, Coyle and a cousin of his from Mississippi. Anders has never met Coyle’s cousin before and will never see him again. He says hi with the rest but takes no further notice of him until they’ve chosen sides and someone asks the cousin what position he wants to play. “Shortstop,” the boy says. “Short’s the best position they is.” Anders turns and looks at him. He wants to hear Coyle’s cousin repeat what he’s just said, though he knows better than to ask. The others will think he’s being a jerk, ragging the kid for his grammar. But that isn’t it, not at all – it’s that Anders is strangely roused, elated, by those final two words, their pure unexpectedness and their music. He takes the field in a trance, repeating them to himself.

The bullet is already in the brain; it won’t be outrun forever, or charmed to a halt. In the end it will do its work and leave the troubled skull behind, dragging its comet’s tail of memory and hope and talent and love into the marble hall of commerce. That can’t be helped. But for now Anders can still make time. Time for the shadows to lengthen on the grass, time for the tethered dog to bark at the flying ball, time for the boy in right field to smack his sweat-blackened mitt and softly chant, They is, they is, they is.

It’s true that this collection is fueled by the threat of violence, fear, and loneliness. Wolff understands that this tension is required to keep us reading. We are human, after all … every one of us will die some day. This is enough of horror, Wolff seems to argue. In the meanwhile, why not make time to sit together around the campfire and tell a few tall tales?

This is honest, empathetic, heartfelt storytelling. It’s fitting that the author includes us – the reader – right in the title of his collection. These are “our” stories, indeed.

[…] review was originally published at Zouch Magazine) This review is one in a series for what I’m calling the The DIY MFA in Creative […]