Woody Allen’s Quantity vs. Quality

Culture, Film, ReviewsWoody Allen has written and directed a movie roughly every year or two for the past several decades. It is a prolific offering rivaled by very few; in turn, the very best of Allen’s oeuvre comprise a legacy that is in a league of its own, helping to define comedy and character-driven narrative, as well the significance of the auteur in contemporary film and theatre. He has produced great and terrible movies in each of the past four decades, and the consistency of his output, combined with the wavering consistency of its quality (particularly, of course, in recent years) makes the legendary director a great case study for the question of quality versus quantity when examining the merit or influence of a celebrated body of work.

This has been a particularly interesting decade for the aging icon. There have been moments of brilliance (Vicky Christina Barcelona in 2008, and the lesser, though more acclaimed Match Point in 2005) as well as some truly awful ones (Whatever Works, his 2009 Larry David vehicle, which is utterly unwatchable). But for the most part, it has been a decade of half-decent though largely forgettable features like You Will Meet A Tall Dark Stranger, which is currently in theatres. And every time another one of these not-great pictures is released, it gives the reviewing community another opportunity to remind the world that Woody’s films just ain’t what they used to be. Fortunately there have been enough gems throughout his illustrious career that he isn’t haunted by a particular former glory, in the same way that say, Nas is cursed to have Illmatic mentioned in everything written about him for the rest of his life. We know that Woody still has greatness in him, but simply lament a time when the clunkers were much fewer and farther between, and his voice was one of undeniable originality. Thus, it would seem that the quantity of his output in recent years has tarnished even further a legacy that started to falter around the time that personal scandal began to garner more attention than new work.

At the same time, who are we, the (sometimes) adoring audience to question the method to Allen’s madness? This is a man who got his start writing 2000 jokes a day for a local New York paper. He has a creative well much, much deeper than the average prolific genius, and it seems clear at this point that Woody will continue to write and make art until he finally gets all of his questions about death answered, once and for all. To slow him down would be to artificially impose a writer’s block that simply doesn’t seem to exist. There’s nothing to say that an eight-year gap between films would necessarily increase the quality of the artist’s work either. Allen is simply not a writer that labours endlessly on his work. Perhaps a more discretionary eye would have spared us a few of his more dreadful works, however his perpetual-motion method is one that has continued to produced works of landmark quality and originality, and as such demands a certain degree of forgiveness.

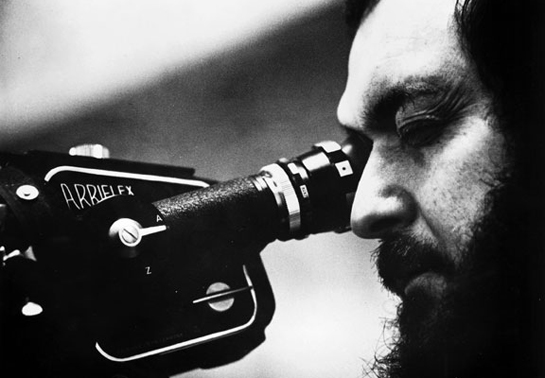

Conversely, Stanley Kubrick, one of the undeniable geniuses of contemporary cinema, has a frustratingly small body of work, particularly from the last two to three decades of his life. While the sparse catalogue serves to accentuate the brilliance of his masterpieces (2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Full Metal Jacket) it removed Kubrick during his later years from the sort of immediate cultural relevance of a director carving his generation’s artistic vision, like perhaps Martin Scorcese or even Stephen Spielberg. It also made his disappointing final film, 1999’s Eyes Wide Shut, fall with an even louder thud, twelve years after its predecessor. While by no means a critical failure, and often considered brilliant in it’s own right, the film simply failed to live up to the anticipation created such distance between his previous works, particularly given that his only other two movies from the preceding twenty-four years were The Shining and Full Metal Jacket. Woody Allen’s shortcomings don’t hit us as hard; at this point, they are almost expected amid other strokes of greatness and average-ness. Determining which legacy holds more merit is perhaps impossible, but they are nonetheless interesting to compare.

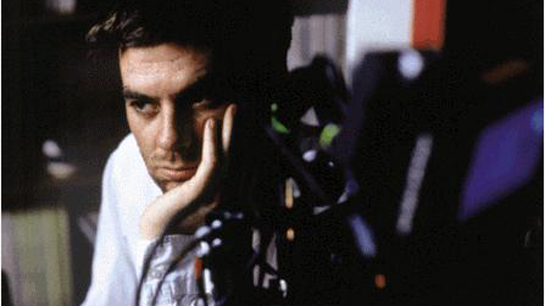

This generation’s two premier auteurs, Paul Thomas Anderson and the Coen brothers, seem to be each following a different one of the two respective paths. Joel and Ethen Coen have put out an impressive body of work in just over twenty-five active years as filmmakers. While the early 2000s seemed to suggest a faltering of the brilliance that produced a number of sometimes funny, sometimes grim, almost always violent masterpieces, they returned to form in the latter half of the decade with No Country For Old Men, which earned their first Best Picture Oscar (and was immediately followed by the very average Burn After Reading). They seem to share Allen’s drive to constantly work and produce, despite occasionally falling short of greatness. Anderson, on the other hand, has written and directed only five films in his fifteen-year career (Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, Magnolia, Punch Drunk Love and There Will Be Blood), and only two in the past decade. Each one has been, arguably, a work of sheer genius and audacity. However, he now faces somewhat of a Kubrickian trap: while not necessarily as immediately recognized for his work as more prolific directors, the pressure on each of his eagerly-awaited pictures is tremendous, and the impact of a failure would be that much more devastating.

There isn’t a right or wrong method or ideal level of artistic output, however considering the dichotomy between quantity and quality as a measure of artistic legacy creates an interesting template to examine the varying processes of these filmmaking greats. It may be observed, of course, across artistic mediums (perhaps nowhere so obviously as in music) and provides but one more satisfying outlet for our culture-obsessed need to index the world around us. I will continue to watch every one of Woody Allen’s films until he’s no longer able to make them, and will of course take the bad with the sometimes still really, really good.