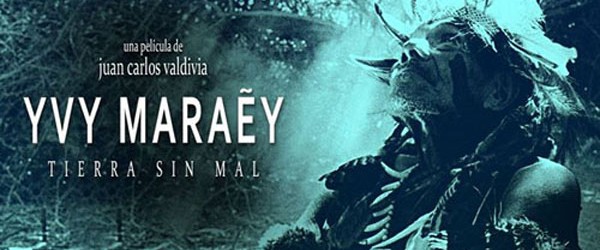

VLAFF 2014 Review – Yvy Maraey: Land Without Evil

Film, Reviews

Juan Carlos Valdivia’s Yvy Maraey: Land Without Evil, is a vibrant, poetic exploration of identity. Lush with myth, cosmogony, and Cartesian dualism, the film presents dualities embedded in Bolivian perspectives—the primary dichotomy being the “karai” (I believe this generally means “white man”) vs. the Guarani, an Indigenous people—only to show the porousness of these boundaries, unified by stories of origin and death.

The binary of the “karai,” played by Andres (Juan Carlos Valdivia, the director himself), and the Guarani, represented by Yari (Elio Ortiz), forms the basis for the friction that enlivens other dualities such as the act of creating and that of being created, thinking and feeling, light and darkness.

In the trail of the Swedish explorer Erland Nordenskiold, whose 1911 ethnographic film documented the Guarani “savages,” Valdivia leaves his home of sixteen rooms and stylizes himself in a caricature of a wealthy explorer (he drives a Jeep) to make a film about the Guarani people as well. But Valdivia is not as superficial as he first seems. Soon after the opening, which poses meditative questions and statements such as “Is thinking the same thing as feeling?” and “There is nothing to know because everything is invented,” Valdivia is on screen, in his house, talking about this very film he wants to make. Self-reflexivity creates space for understanding the difficult task that is making a film about the Guarani people; Valdivia later claims “Cinema is a weapon.”

As the film progresses, the dialogue between Andres and Yari brings to light myths, traditions, histories, all of which are presented in the wholesome way of good conversation, with a fraternal streak of humour vivifying the seriousness. Though Valdivia’s expression doesn’t change much throughout, the film compensates for this with a roving camera, allowing the viewer to feel discovery and movement in the landscape itself, emphasizing continuity and the malleable constructs of identity.

There are many sequences in which an unnamed narrator speaks among what seems to be the undergrowth of the forest. The narrator says: “in the darkness we find our origins.” This line guides the most memorable part of the film: Valdivia in the dark, walking through a swamp, the music is a sharp, tinkling cacophony of forest sounds, and everything is urgent and alive, saturated in dark blues and greens and blacks.

It is possible that Valdivia’s self-reflexivity and philosophical statements may be seen as pretentious, superfluous. But for those without a Jeep—who happen to do their exploring in books, as opposed to on the road—these layers add another dimension, which also build on the role of storytelling and the “word” in creation myths, and identity formation.

Ultimately, the film could have benefited by tightening up these techniques, which feel secondary to the exploration of the Guarani people. Regardless, I appreciated the attempt to posit cinema as a destructive force, the role of the director as a hindrance to the veracity of the tale, and the creative process as one of negotiation. I will certainly be keeping my eyes peeled for the next film by Juan Carlos Valdivia.