In The Veins of Amy Guidry

Artists, InterviewsAmy Guidry is an American artist from Lafayette, Louisiana. She grew up in Slidell, Louisiana, a suburb of New Orleans. Guidry’s work has been exhibited in galleries and museums nationwide including the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, the Alexandria Museum of Art, the Women’s Research Center at Brandeis University, and the Acadiana Center for the Arts.

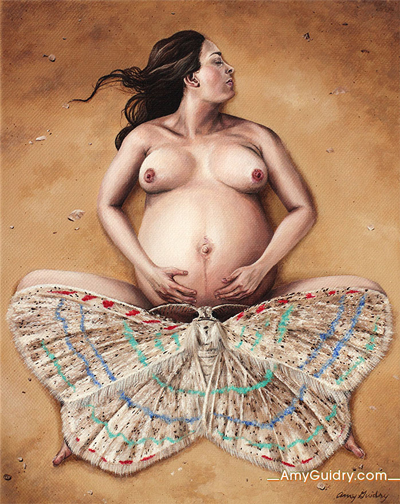

“In Our Veins” explores the connections between all life forms and the cycle of life. Through a psychological, and sometimes visceral, approach, this series investigates our relationships to each other and to the natural world, as well as our role in the life cycle.

Zouch Magazine’s Jeff Campagna caught up with Amy recently and asked some questions about life, death and art.

You mentioned that In Our Veins is about the connections between us and the natural world we live in. What inspired you to create the series? Can you narrow it down to a specific moment?

“In Our Veins” was really more of a natural progression for me since I am a vegan (12+ years- I was a vegetarian for several years before then) and animal welfare is a significant issue and on my mind most of the time. One of the themes explored in this series is animal welfare since it is also ties into the future of our environment. They really go hand-in-hand. “In Our Veins” explores the connections between all life forms and the process of the life cycle. This includes the interdependence of the human race to each other and to the rest of the animal kingdom, as well as the planet itself. One cannot exist without the other, therefore it is of the utmost importance that we care for each and every living thing. If one is removed, there is a domino effect that eventually makes its way to us. Nature is a very delicate balance.

The pieces have a very surreal quality to them. What is the specific artistic process behind creating the works?

I’ve been influenced by Surrealism from a very young age. Besides art, psychology was another interest of mine and since Surrealism is the grand marriage of the two, I was naturally drawn to it. My style has become progressively more surreal, and I am always looking to challenge myself both technically and conceptually. As a result, with my latest series “In Our Veins,” I have been working with ideas that come from my dreams and free-association exercises, both of which were utilized by the original Surrealists. I’ll sketch ideas from dreams or sometimes I’ll just think of a concept, a word, etc. and see what images come to mind. I try to block out everything else and let my imagination wander. Usually at night when I’m just starting to fall asleep is when I get a lot of ideas, which is why I keep a sketchbook nearby so I can jot down anything that comes to mind.

When someone walks through the gallery and spends time looking at each piece of the In Our Veins series, what do you hope they take away from it?

Well, the first thing I strive for is to get my audience’s attention, so if they stop and really look at each painting, that’s a good sign. I use my work as a platform for tackling issues of personal interest. Art is my way of communicating with the world, raising questions, and presenting ideas. I rely on it to get people thinking and hopefully inspire change. I can’t tell people what to do, but I hope that my work will at least inspire them, get them talking, and encourage them to reflect on what they can do to help make a difference in the world.

Most of the pieces contain floating head imagery. What significance does the ‘head’ of a being hold?

Many people view nature as a means to an end. Animals are treated as pieces and parts and labeled as such- head, tongue, rump, rear, breast, wing, etc. Even when they are not referred to simply as parts, they are named something other than what they are- chicken is poultry, pig is pork, cows are beef, etc. They are no longer acknowledged as animals, but as food. Others are trophies to hang on a wall, or turned into luxury goods. I see animals as sentient beings. While many people just see a head, for instance, I depict them with personalities, or what others arrogantly deem as “human” qualities (as if only humans can express emotions). Many of the animals I depict have eyes that look more “human,” in that you see the whites of the eyes, or they have blue, green, or amber colored eyes and not large, dark doe eyes as typically associated with animals. In some paintings, animals are seen in a dominant stance or their facial expression is calm and serene or they are staring directly at the viewer, demanding attention and acknowledgement. Again, these are all qualities typically associated with humans, however, I see these as qualities in other animals as well.

What’s next?

Right now I’m expanding upon the “In Our Veins” series and preparing for several upcoming shows- a group exhibition at Wally Workman Gallery in Austin this December; a solo show at the Slidell Cultural Center in February/March of 2012; and a four-person exhibition at the Hilliard Museum in Lafayette, LA in the Fall of 2012.