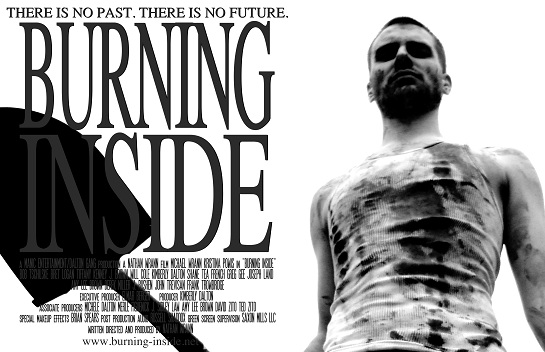

Extended Short Circuit: Nathan Wrann’s “Burning Inside”

Culture, Film, Reviewsby Bjorn Gabriels

How sweet it is. In the Walhalla where major art themes gather, revenge dwells – its teeth grinding and eyes screaming with wrath – near love and betrayal. It is at once a sacred monster and a vibrant force propelling such diverse film genres as classic American westerns, Asian horror flicks or your average romcom television drama. More often than not, this leads to a piece of cinema biting its own tail: you know the beginning and the end, but somewhere in the process you have managed to get yourself stuck. Connecticut-based director and writer Nathan Wrann avoids these pitfalls with electrifying poise in his second feature film, Burning Inside.

Everyman

Burning Inside’s opening scene immediately lays bare Wrann’s intentions. In a static shot that lasts several minutes, a nurse shaves a comatose patient confined to a bed in a sparsely filled hospital room. After a brief moment the colored images jump to a highly contrasted black and white. The patient (Michael Wrann) eventually awakes and, because he doesn’t seem to be able to shed light on his identity, receives the apt name John Doe. Although his psychiatrist stresses that he should be able to communicate, John keeps his silence. Even if he remembers what has happened to him before his rude awakening, he doesn’t let anybody in on his thoughts. This doesn’t hinder the caring nurse Jennifer (Kristina Powis) from talking to him, keeping him company and eventually – against the strict orders of the villainous doctor – taking him on a trip that will hopefully trigger John’s memory.

As soon as John rises from his immobile state, Burning Inside becomes a quest for his identity. The many blanks in his memory are gradually filled, especially when he and Jennifer start living together in a house that seems related to his past. Jennifer craves homely happiness together with John, and she will carry a child from her patient in distress. John, however, is far from innocent. For reasons that remain unclear at first, he undertakes a mission of revenge. As the contours of John’s identity are shaped out more clearly, the motivations for his tour of retribution sneak in.

Hunting Season

In his first feature film, Hunting Season (2006), Nathan Wrann worked within the generic confinements of the slasher to – in his own words – explore ‘the cyclical nature of revenge’. The bloody confrontation between two hunters and a group of teenagers (neatly divided in three boys and three girls) is set during a camping trip to a distant part of a private property. Wrann chose to shoot his film entirely with a hand held camera, a stylistic feature of many a ‘killer chases victims through the woods’ films.

In Burning Inside he has opted for an entirely different approach. Wrann no longer drags his camera over roots sticking out of dirt and dead leaves, but shoots most of the scenes with his camera steadily secured on a tripod. To further deviate from the look and feel of his debut, he decided to stretch his shots to a length seldom applied in genre films with ruthless avengers frolicking about. This departure from his preferred cinéma vérité-style also made him opt for a film largely shot in very expressive black and white.

What does return in his second movie – revenge always comes back for more – is his focus on the motivations and the consequences of vicious retaliation, this time adding the impact of a failing or at least selective memory into the mix. Much more than Hunting Season, Burning Inside manages to tackle a gray zone so often neglected in genre cinema. It deviates thematically, structurally and formally from the paths worn down by a staggering pack of homicidal maniacs and their ever so innocent victims. Stemming from films like David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977), Burning Inside seeks close encounter with the illustrious midnight movies of the seventies, a rather unrelated collection of innovative underground films combining a lust for experiment with the conventions of genre cinema. Even a brief glance at some of the most renowned films of this wild bunch shows their diversity. Besides Eraserhead and John Water’s Pink Flamingos (1972) – films that almost created their own genre – there was George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), which planted an injection of vitality between the ears of the zombie film. The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Jim Sharman, 1975) then feasted upon musical and Gothic horror. And Alexander Jodorowsky, the self-proclaimed inventor of the midnight movies, unearthed El Topo (1970), a violent spiritual western. All in all, those film makers ‘keenly disturbed’ rusted down film genres by purposefully challenging themselves and their audiences.

And to this ‘loose’ tradition relates Nathan Wrann’s Burning Inside. It is only befitting that the distribution company that releases the film is named Channel Midnight. If its name is no clear omen, their motto explicitly states their intent to distribute ‘genre film without compromise’. In taking Burning Inside aboard, they seem to live up to their mission statement to release ‘smart, non-traditional genre cinema’.

Merciless memory

Initially, Wrann intended to write a rather classic revenge film. While working on a new scenario the fixed patterns were unable to aptly translate the ideas he wanted to weave into his film. Especially the role memory plays in the chain of revenge pushed Burning Inside to other regions: ‘One of the aspects that I kept coming back to was the fact that revenge is based solely on memory. If the initial victim doesn’t remember the evil that was done, they have no inkling to get revenge. I challenged myself to write a revenge story around a character with amnesia.’

Despite his loss of memory, John Doe embarks on a journey of revenge. Following his footsteps, viewers can gradually puzzle together why John – at first an immobile and silent patient – begins his wrathful roaming. Burning Inside’s slow, almost comatose rhythm increases the tension and offers (practically forces) viewers the time and space for reflection.

Other revenge films, including those following a more conventional outline, have taken up the challenge to question the nature of revenge. Wrann himself has pointed towards the Wes Craven classic The Last House on the Left (1972) as a prime example. In that film, Craven has child murder and abuse boosting an act of retaliation by previously innocent parents. The Last House on the Left shows that at the core of vengeance lies the brutal intrusion of personal freedom or a state of happiness often related to the domestic realm. Some form of mistreatment (survived by the victim or his peers, offspring, partner…) is the starting point of – and the main reason for – an increasingly fierce series of retribution. Oftentimes, the ensuing cascade of violence is justified by this clear-cut, horrendous crossing of the existing moral boundaries without questioning the act of revenge in itself. Those violating the current rules of order first, cross a line, and once over yonder they can’t count on mercy.

Low resistance

Of course, not all revenge films are trapped in this black and white pattern. Neither do they all wind up in the dead end street of so-called torture porn. One director who masters the craft of violent cuts but also deals with the double-heartedness of violence is Sam Peckinpah. In an interview with Slant Magazine Nathan Wrann has mentioned Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) as a source of inspiration. In that film, an American mathematician (Dustin Hoffman) travels with his English wife to the British countryside to be at ease and work on a future publication. This inept, passive-aggressive man will later see himself forced to defend his home, where a mentally handicapped child molester hides himself, from a herd of spiteful townspeople. Only just before, his wife (Susan George) was violated in that same house, while he was abandoned by some robust men during a hunting trip on the moors. Peckinpah attaches his long stretched spiral of brutality – from verbal innuendos to outbreaks of physical violence – to a (failing) virility, voyeurism, apathy and the family nucleus constructed around husband and wife. Straw Dogs then becomes a reflection on the inherent presence of violence in individuals, personal relationships and society as a whole. Running away from urban America to the rural countryside in England doesn’t affect that. Nor does a flimsy layer of civilized pacifism, according to Peckinpah.

The thematic kinship between Straw Dogs and Burning Inside doesn’t immediately translate into an overt visual similarity. In general, Peckinpah opts for a crisp montage, whereas Wrann chooses longer, static shots. Yet, two pivotal events demonstrate a striking resemblance. In a controversial scene halfway Straw Dogs, Peckinpah shows how the English wife is violated – a first time by an old friend, in an estranging hybrid of rape and adultery, then directly followed by an evident violation by another villager. This scene is inter cut with images from her husband shooting down a bird for the first time in his life. He weighs the bird in his hands, decides to leave it behind anyway, wipes off his blood soiled hands and returns home. His wife doesn’t inform him about what has only just happened to her. It is clear that the traditional romance of the English old boys’ network hunting in an idyllic countryside disintegrates before our eyes. Creeping under your skin or facing you head on, violence always finds it way.

Although Burning Inside is largely composed in extended shots, Wrann has included a remarkable montage. (Consequently standing out even with even more vigor.) About halfway in the film, John Doe initiates his revenge. The images of him performing his first killing are interwoven with an intimate scene between John and a pregnant Jennifer. To place even more emphasis on this scene Wrann – who fills his soundtrack sparsely – plays Schubert’s ‘Ave Maria’. Wrann’s cutting isn’t as graciously fast paced as Peckinpah’s, but through the use of slow motion and overtly extended, overlapping dissolves this montage blends well into the rhythm of his film. The repetitiveness and lingering drama of ‘Ave Maria’ provides the scene with a mixed tenor of grandeur and alienation.

This montage portrays John Doe as an avenging angel and troubled husband. The confined space inhabited by his closest relatives and the violence erupting on the outside are intertwined. Perhaps not overtly present, yet the typical traits of the revenge film manifest themselves in Burning Inside. An idyllic state is breached, which invokes the machinery of revenge to start its slow, grinding turn. The executioner measures the weapons for his revenge (not as plain and open as Bruce Willis’ Pulp Fiction character does in the pawn shop, but still). The retaliation then happens in different stages – befittingly, the ‘guilty victims’ don’t meet their fate at the same time or in the same place – and preferably in a vicious manner. Burning Inside, however, stretches these archetypical elements out to the utmost limit so that the actual deed of vengeance almost becomes a secondary act. It takes place, but the true engine of the story is the quest for John Doe’s identity and his motivations.

Grey zone

In order to articulate the inner world of his main character, Wrann has opted to shoot Burning Inside in a very distinct black and white palette. By resorting to highly artificial lighting he creates contrasting areas of brightness and darkness with long shadows that remind of German Expressionism classics. Wrann has acknowledged this influence by saying that, when feeling jammed while writing his scenario, he decided to start painting from images of famous black and white movies such as Night of the Living Dead and Nosferatu (F. W. Murnau, 1922). Crafting these stark contrast paintings brought him to the aesthetic of German Expressionist cinema, which had originated from the limited financial means available during the twenties in Germany. This expressionistic framework eventually found its way into the visual style of Burning Inside and proved accurate in shaping the look and feel of his film. ‘The black and white German Expressionist style works really well on many different levels to tell John Doe’s story, whether it’s from practical, production considerations to symbolic meaning to timelessness, to how the audience perceives the “reality” or “fantasy” of black-and-white compared to color.’

Wrann’s approach to film making is often – of necessity – directed by a mix of practical restrictions and artistically inspired choices. In the case of Burning Inside this ‘if you can’t pay the piper, there’s no tune’-method has paid off. For pragmatic reasons Wrann also opted to make an almost ‘silent’ film. This decision matches well with the expressionistic aesthetics, but is equally inspired by his experience laboring on the soundtrack of his debut, Hunting Season. His second feature then became a film with sparse dialogue and a highly selective use of background noise or music. This opens up the field for its mechanically manipulated soundtrack, which is reminiscent of the work sound designer Alan Splet did for David Lynch.

The most telling features of Burning Inside are therefore born out of limitations enforced by practical circumstances. Yet, in the end, all those decisions mold into a consequent cinematic vision: ‘I don’t know if it [the static camera] creates tension on its own, but combined with the constant sound, black-and-white, long cuts, overall lack of dialogue and mystery of John Doe, […] it takes the audience out of their comfort zone.’ After dealing with technical restrictions himself, Nathan Wrann intentionally challenges the audience and forces them to leave their comfortable positions. Unlike many other revenge films (or other films portraying violence, for that matter), the uneasiness here is not so much provoked by the physical representation of violence (or its suggestion) as it is formed by the time and space Burning Inside offers to waver over one’s expectations and ideas. Perhaps not everyone will be persuaded to sit through Wrann’s slow cinema, but… in constraint he first shows himself the master.

Darkroom

There’s no need to reveal here what makes John Doe tick, even though Burning Inside proves to hold much more than the tension of a whodunit or ‘whoisit’. Interesting in this respect is that the tension building up is strongly related to ‘energy’, which seems to connect various motives. First of all, there is the industrial sounding score brooding under several scenes. On the visual field, lights are wired through Burning Inside. The transition between scenes is mostly marked by the screen filling sight of a lamp. This light source is introduced at the very beginning, as the opening shot shows a light hanging over a hospital bed. This camera standpoint is then reversed – the camera takes over the position of the light bulb – in the ensuing first scene, in which John Doe rests in his bed. From this moment onwards, that blinding light source keeps on burning. Later in the film this visual motif is connected to the lenses of a photo camera and a hand-held film camera. Thus linking light, energy, with mechanisms that are an addition to (or a replacement of) our memory.

The process of scraping John Doe’s memory to find out who he is, is largely mediated by photos and film stock. After John has drawn a landscape – possibly from his past – on his hospital room wall, nurse Jennifer encourages him to delve into his past through images. She gives him a photo camera hoping that John can record the present – and most chiefly the prospect of their future lives together – never to forget. The house on the countryside where patient and nurse live as a couple and its surroundings indeed resemble the landscape John penciled on the wall. Only the two crosses he drew earlier seem to be missing. While roaming around, John finds a film camera with some film in it. He processes the film in his workplace and projects it on a blank screen. The images offer a gateway into John’s past, or rather: reflect his train of thoughts.

The succession of the pencil drawing, the Polaroid pictures and the moving images – a chain marked by an ever increasing mechanical process, needing energy to develop – seems to offer an insight to John Doe’s identity. This procedure can even be taken to a next level as the film Burning Inside itself also becomes part of the equation. Wrann has edited and modified his film in such a way that it stresses the film as an object in its own right. Besides the conspicuous scene transitions through light sources, he also uses deliberately ‘artificial’ techniques such as slow and overlapping faders, sudden jump cuts or irregular camera standpoints. This results in Wrann explicitly renouncing every attempt to uphold the illusion of reality as installed by a more traditional montage. Adding to this, he had his film material modified so that it looks like an aged film.

All these techniques seem to suggest that Burning Inside is an account of a subjective experience, a past personally modified and colored in. The driving force behind this traumatic experience is a ruthless energy. Revenge appears to function like electro shocks do: do they offer an atrocious cure or are they an everlasting torture? Whichever way, at the core of Burning Inside simmers a personal tragedy of a complex character whose circuit is irreparably damaged.