{Review} Sly Silly Creativity: Dorfman’s “Prophets of Funk”

Art, Art News, ReviewsIf it’s true that the artwork of a dance is found in its performance, then everything depends on when and where that performance begins. And that depends in part on the viewer. For me, David Dorfman Dance’s “Prophets of Funk: Celebrating the Music of Sly and the Family Stone,” began in the high school gym of Restoration Academy, a K-12 school in the Birmingham metro area (three miles from my grandmother’s house). Here, where it’s harder to pretend that the challenges the Family Stone confronted are past, Dorfman finished a three-week tour of the western Southeast with a four-day residency. And much like the white New England schoolteachers whom Du Bois praise in The Souls of Black Folk, Dorfman’s company spent most of their time teaching classes at predominantly working class, African-American schools.

Restoration was the last such school, where Dorfman and his eight company members joined several dozen boys and girls (along with Sean Wright, the cheerful Director of Venue Management for Samford University, host institution for the show). Beginning in a circle, Dorfman explained the concepts of symmetry and asymmetry, then led an icebreaker exercise in which each student performed a unique movement to the music of her/his name. The silly creativity that ensued set the tone for the rest of the hour, mostly spent in small groups, with the company members exhorting the children into collective choreography. The finale was the performance of their brief routines for the class, some accompanied by Dorfman, sporting an accordion half his size, and synchronizing the room with Creole and Argentinian rhythms. After class disbanded, the company lingered, with the agile Bryan Strimpel dancing a soccer ball just out of the reach of one delighted boy, and Dorfman shooting hoops with several others.

The Second Act of this extended performance was the final rehearsal that evening, at Samford University’s Wright Center. If anything, it was even sillier and more creative than the class. Highlights included Karl Rogers tumbling like a Thai wicker ball down the length of the aisle, and several dancers riffing a string of pirouettes, the difficult variation being pausing between each one en face, with the right leg in retiré devant. Also making a return appearance from the First Act was the gentleness, this time among the members themselves, as when they occasionally lounged in pairs into on-stage massages, kneading the dough of weary muscles for another rise.

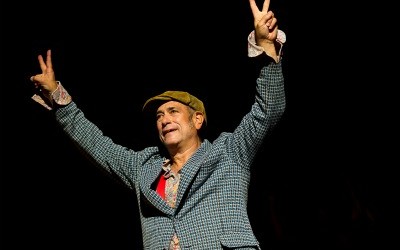

The Final Act was the following night at 8 p.m. “Prophets of Funk” begins with Dorfman, in his late fifties, strutting onto stage wearing a costume composed of his own teenage disco wardrobe—platform heels included!—and piling on a smorgasbord of front kicks, arm flails, and booty-shakes (to a laugh track soon drowned by the real thing). Next comes Raja Kelly, a dandelion in his gigantic afro, deftly executing the lead role of Sly, followed by the other seven, idiosyncratically-embodied members of this gender- and racially-balanced band (all sporting the trippy-groovy costuming of Amanda Bujak). In the background are Jacob Pinholster’s video clips from the Family Stone’s live performances, interspersed with screensaver-like images including a close-up disco ball and sinuous curl of pot smoke. Punctuating the dancing, finally, are short political speeches, an audio clip from a condescending interview of Sly by Dick Cabot, and extended visual metaphors for the band’s professional, romantic and psychotropic escapades.

As for the dancing, its central gestural argument appears to be that sly-silly creativity is a powerful tool for renovating the house of social justice. One of three supporting premises for this argument is that politicized humor produces resilience in the face of oppression. The most effective deployment of this humor is an interlude in which Nik Owens’s character charmingly educates the audience in a series of satirically-titled moves (my favorite being “the cracker”), declaring of each: “That’s my move!” Despite all the excitement, however, the other characters “fall asleep” in the middle of the lesson, then leave him to recount (in a deeper octave) a series of painful losses—while nevertheless exulting: “I’ve still got my funk!”

A second supporting premise is that orthodox movements can be playfully distorted in politically-liberating ways. Of the many funk inflections, beading like sweat on the dance’s balletic, modern and postmodern vocabulary, the most prominent is a kind of extra bounce-shake, in grateful surrender to a blast from Stone horns. Though some reviewers have criticize the choreography, specifically on the grounds that it looks more fun to do than to watch, that is precisely the point: a dance that wears its liberation on its sleeve, to tempt the public into therapeutic participation.

And a final supporting premise is that, when not drained of the tenderness spilling over naturally from the dancers’ non-show interactions (including the community classes and rehearsal improvisations), controversial partnering can broaden the audience’s moral imagination. Of the many expectation-defying lifts (including women lifting men, and men lifting each other), one powerful example is that of Kelly (who is black) lifting Kendra Portier (who is white) by the backs of her thighs, then almost-dropping her in a series of strategically awkward embraces, transitioning jagged from expansive ecstasy to fragile implosion, like a beer bottle dropped to the pavement, reflecting more with each crunch of a callous heel. Thus, the potential scandal of black-and-white love shines for the audience as intimately natural, shaming us for the beauty many still condemn.

Thus, Dorfman’s piece is a fitting tribute to Sly and the Family Stone, who laid these tracks for us half a century ago, with outrageous costumes, unprecedented genre-blending, and groundbreaking racial integration and female musicians. At the show’s end, when the audience is practically hauled onstage to share “Dance to the Music” and “Everyday People” with the company, I too boogied bashful, grinning around Sean Wright and the kids from Restoration, and feeling the truth of Dorfman’s claim that his community outreach, academic teaching, and theatrical choreography are all part of one performance. So although it’s true, as Robson’s character says in her monologue, that we should keep “one eye open” for prophets’ deceptive wizardry, we should keep the other eye, in Dorfman’s case, on his exemplary magic: building social justice with the sly-silly creativity of dance.

Thus, Dorfman’s piece is a fitting tribute to Sly and the Family Stone, who laid these tracks for us half a century ago, with outrageous costumes, unprecedented genre-blending, and groundbreaking racial integration and female musicians. At the show’s end, when the audience is practically hauled onstage to share “Dance to the Music” and “Everyday People” with the company, I too boogied bashful, grinning around Sean Wright and the kids from Restoration, and feeling the truth of Dorfman’s claim that his community outreach, academic teaching, and theatrical choreography are all part of one performance. So although it’s true, as Robson’s character says in her monologue, that we should keep “one eye open” for prophets’ deceptive wizardry, we should keep the other eye, in Dorfman’s case, on his exemplary magic: building social justice with the sly-silly creativity of dance.

April 29, International Dance Day: Keep your eyes peeled for J.M.’s exclusive interview with David Dorfman.