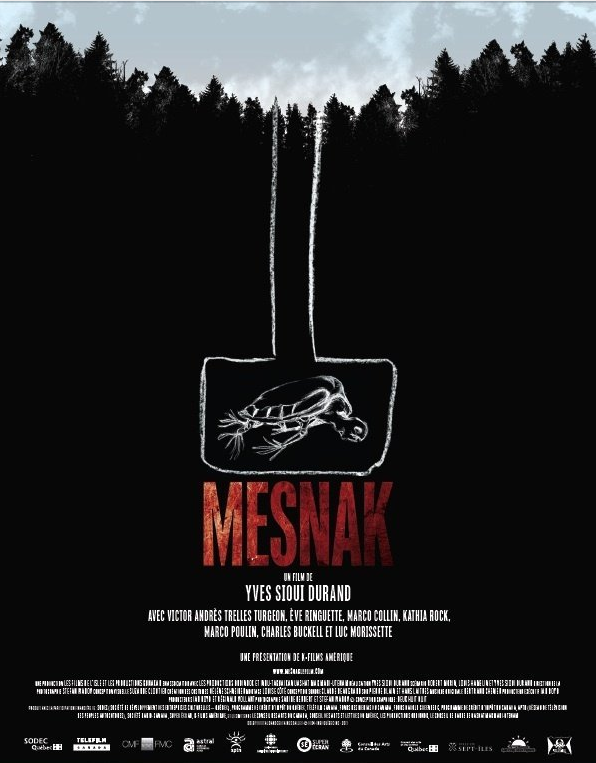

MESNAK, a first trilingual Aboriginal-made feature-length film, teaches us many things

Film, ReviewsThere is a well-known song by Green Day called “Time of Your Life” (1998). This is the kind of experience I had on the 17th of February at the Montreal premiere of the aboriginal-made film Mesnak, directed and developed in Québec by playwright Yves Sioui Durand, a Huron from Wendake just outside Québec City. A worldwide first, this feature-length film made in Québec had been screened and acclaimed at Toronto’s annual imagineNative Film and Media Arts Festival in the fall of 2011.

The party afterwards was a celebration for and with aboriginal and non-aboriginal friends, families, artists, supporters, critics, and media too. The event featured music by Florant Vollant in collaboration with Chloé Sainte Marie, the slam-rapper-activist Samian, and other stars, including one of the film’s actresses, Katia Roch.

That it is easy to misinterpret the film is a result of its beautiful complexity and the way it plays against the conventions of “professional,” mainstream cinema and narrative film structures or stories. Far from unprofessional, Mesnak positions itself bravely, as film within lineages of theatre and visual art, as well as radical cinema, both in French-Québec traditions and in Canada, as well as abroad. Many of the moving images – like that of a teenage girl running swiftly through a black spruce forest in an isolated community of Innu in northern Québec – are simply beyond words.

To situate the film within more predicable, careerist and Hollywoodian aims is an ideological flaw, I think. This oeuvre d’art vivant (work of living art) is more than a conventional fit. Rather, Sioui Durand proposes new ways of understanding the stereotypes that we condemn often from the outside looking in: the substance abuse, incest and poverty that are still realities for many on reserves. What I think Sioui Durand and co-producer Innu Réginald Vollant are proposing is much more important in terms of unity of voice.

First, they are making real alliances across cultures with non-aboriginal and métis peoples, while expressing a uniquely aboriginal voice. Second, they are inviting aboriginal people themselves, living in cities and on reserves, to participate in their own representations, revealing tensions between lived realities and stereotypes. In so doing, they are taking the fate of these stereotypes well in hand. I applaud them for being brave.

I have read both positive and less favorable descriptive critiques of the film. I think that many of the points being made are interesting, but that most of the criticism is simply missing the (most crucial) point: that the film is most important, not because it speaks back or resists; but because of how it speaks. It presents a unique, solid, and cohesive voice, while being mindful of difference. Most interestingly for me, the film does not “ghettoize” or push away whites or other non-autochtonous voices, but rather embraces difference to allow for aboriginal identification and mythologies to be heard. It teaches us many things.

MESNAK was screened at MoMA in New York City on March 17th, and is playing on selected dates at venues and festivals internationally. For more information, or to obtain a copy of the film in its original version with English subtitles, please contact K-Films Amérique at (514) 277-2613 or [email protected]. Also see www.mesnaklefilm.com for more information and images.