{Memoir} This Is My Proof

Literature, Memoir“I believed, by way of contemplating the future, that we would all be around for one another’s funerals.”

– Joan Didion, “After Henry”

When I find out Abe is dead it’s nearly nine months after the fact. But I don’t know this yet.

I take the L-train to the Graham Avenue stop. Legion Bar is a short walk from the subway station. I enter the bar and walk to the backroom. Inside, there’s hardly any light, except for the dimmed stage lights hanging from the ceiling, but I manage to make out my friend Rachel in the back corner of the room. I walk over, and she introduces me to one of the other actresses who will be performing with us tonight in a sketch Rachel has written.

Rachel gives me the skinny on the show—how it’s every few weeks and there’s usually a pretty good crowd—and I tell her how I performed here, at this same show, “probably a year ago.”

“Oh, so you know,” she says.

It was back in June of 2009. I had just started doing stand-up and was unable to win over the audience of cramped hipsters. Although one bit seemed to work: “I came across this Craigslist ad…”—maybe a year or two before the performance—“…that said, ‘Watch me jerk off…No Strings Attached!’”

At the end of my set, I thanked Abe, who was hosting the show, for having invited me. A part of me wanted to apologize for doing such a shitty job. He’d given me all that time—“Like 20 min if you want it, but no requirement to fill that much time”—and I did not deliver.

“Hey, where is he?” I say. “Where’s Abe?”

“Abe?” she says.

“Yeah.”

She takes a beat. “Abe died.”

I wait for the punch line—it’s not uncommon for comedians to fuck around about death—but it doesn’t come.

“Wait.” I say. “How?”

“I don’t know,” she says. “He just died.”

I take a moment—look around the room. There’s no audience yet. Maybe I remember the two pictures my girlfriend took with her iPhone when I last performed here: June 11, 2009. It was before the show, the audience had yet to arrive—the chairs weren’t even set-up yet. The raised stage—no more than six inches off the ground—was lit in this pale red light, the color of faded brick.

In one picture the stage is empty, except for a chair, a bench, and a stool. In the other picture the stool disappears, and the bench moves away from the chair. In both pics, two stand-less microphones seem to be captured slithering onto the stage.

Minutes later, Rachel introduces me to Deepak, who is now hosting the show. “You look familiar,” he says. “How do I know you?”

I tell him that I performed here, “like a year ago—when Abe was hosting.”

“What’s your name again?”

I tell him.

He gets excited. He does remember me. “Oh, we have to have you back here to perform!” he says.

I notice the projector screen on the back wall of the stage is down. On it the name of the show has been changed from Admixture to Abemixture. When I last performed here, they had to drape a white bed sheet along that brick wall, so they could show this female comedian’s video that had been uploaded to YouTube. The clip had something to do with cats and inside jokes only the comedian and her friends and family in the audience knew. The projection of the video was badly distorted because of the creases in the sheet—but the audience loved its comedian. She and the video killed.

Only towards the end of the show did Abe realize that there was actually a projector screen on the wall; the screen was hidden behind the valence of the stage curtain. There had been no need for the bed sheet.

Abe was self-deprecating and, dare I say, cute about his mess-up. He seemed to shine in that moment of awkwardness: stripping the brick wall of his bed sheet. But then again, every time he had gotten on stage that night to introduce an act, he was awkward (but not always with a shine).

I ask Deepak what happened to Abe, and he says it’s a long story—that he’ll tell it to me later, after the show.

There are people sitting in chairs now—an audience—and the show is about to start. We’re the first act up. The Sketch: two Miss-America finalists are on stage during the question-and-answer round. The Conceit: the audience can hear what the contestants are thinking.

Rachel and another actress—the Contestants—stand on stage. The actress, whom I met earlier, and I—the Voices in the Contestants’ heads—stand off to the side of the stage. We are not hidden from the audience. We share a script and a microphone.

The Voice in Contestant #1’s head is feminine, gentle, and reassuring. The Voice in Contestant #2’s head is grating, harsh, and Paul Lynde. (I do a pretty good Paul Lynde.)

There are laughs where there should be laughs—e.g. whenever Paul Lynde reminds Contestant #2 how unworthy of the crown and awful of a human being she is. The blackout line needs work. (I tossed in an adlib at the end of the line that was just not funny.)

Exeunt.

I apologize to Rachel for the adlib—I shouldn’t have done that. I wish her luck on the other sketches she’ll be putting up tonight, and then leave the bar—before Deepak can tell me what happened to Abe.

*

On the train ride back to Manhattan, I try to remember Abe. There’s not much to remember—I hardly knew the guy—but I feel like it’s something I have to do. I have to remember him. Our brief encounters have somehow bound me to this relationship I could never have foreseen. I’m still alive, so the burden’s on me to remember.

Abe and I had performed at a mutual friend’s variety show on the Lower East Side called Street Meat. That night I read an erotic story I’d written about my (fictional) grandfather’s one-night sexual romp with a black GI at a dancehall in France during World War II. It was in the form of a letter “my grandfather” had written to my (fictional) grandmother Gertrude.

A day or two after the Street Meat show, Abe emailed me: “I really liked it, certainly a hard act to follow!” For Abe’s S.M. set he did some lip-syncing to a Hip Hop song, which I can’t remember. I wasn’t sure what he was doing up there—if Abe was doing an impression of Joaquin Phoenix, who, at the time, was masquerading (and not fooling anyone) with his fucked-up-actor-turned-rapper bit—but it wasn’t funny. That didn’t matter to me, because Abe extended an open invitation for me to perform at his show, Admixture, in Williamsburg. It was stage time—a real show, not an open mic—and I was grateful.

*

When I get back to our apartment, I tell my girlfriend how the sketch went—about the blackout line. “And guess what…” I say.

She’s sitting at her desk. I’m standing before her, my feet planted to the floor. She’s my audience. I walk her through my evening and its authentic yet boring dialogue. I’m trying to build up to the news of Abe’s death, but I give up.

She asks if I know how he died.

I tell her I don’t know—how I’ll try to get in touch with Deepak over Facebook or something. More than anything I try to explain to her what I’m feeling—I try to make sense of what I’m feeling. “I didn’t even know the guy,” I say. “I just did his show.”

Abe feels like a fabrication—a montage my brain has spackled together. Abe is a lip-syncing bit gone unfunny. Abe is an unnecessary bed sheet. Abe is an empty stage.

And I’m afraid I’m not too different from that. If our roles were reversed—Abe’s and mine—how would he remember me?

*

Later, I find Deepak’s profile on Facebook and shoot a message to him. Soon after, I go to Abe’s Facebook page—we are (still) Facebook friends—and see comments as recent as the day of the Abemixture. One of Abe’s friends wrote about going to a favorite spot of theirs, but “…i had to leave cause i wished you were there too badly…” Another friend wrote, “Summer isn’t the same without you.” In March, a friend posted a link to a New York Times article on Abe’s Wall: “ABE, Pioneering Robotic Undersea Explorer, Is Dead at 16.” I follow the post dates back, past birthday wishes and missing-you’s—back to what might be the last comment Abe left on Facebook: “Yes. Thank you!”

I feel weird having this access to Abe. I click through photos (ones he posted and ones he was tagged in). There’s a two-picture series that I like very much: Abe and his family are decked out in Red Sox shirts. In one picture the family faces the picture-taker—they all look like Abe! And in the next picture, their backs are to the camera, and their last name is stamped red, thick, and permanent across the dark-blue fabric below their shoulders.

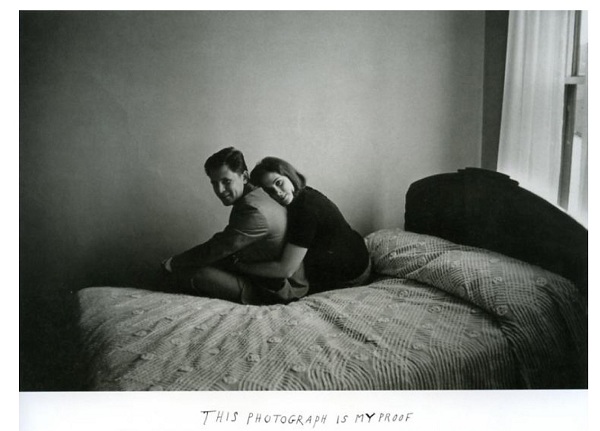

One of Abe’s profile pictures is of artist Duane Michaels’s “This Photograph is My Proof.” In the black-and-white shot, a man and a woman sit on the edge of a bed in what looks like an otherwise empty room. The two figures face the camera. The man has a slight smile, as his companion embraces him from behind.

The photo was accompanied by text:

This photograph is my proof. There was that afternoon, when things were still good between us, and she embraced me, and we were so happy. It did happen, she did love me. Look see for yourself!

In Abe’s version, the text has been cropped out, but the photograph’s title remains. Again, “This Photograph is My Proof.” I don’t know why Abe cut out the text—maybe that was the first version he came across when he Googled the image—but the presence of the piece on his Facebook page is telling. Because what is a Facebook account but proof that you were here? That this happened!

I have videos on YouTube, a blog that is unfrequented, and a Twitter account I’ve combined with my Facebook account, so that my tweets appear instantaneously on my FB page. I’ve bombed on stage, done my best Paul Lynde, given thanks to the host. I was here! This happened!

I’m trying to think of jokes. There’s the one about me sending Abe a Facebook message in February of 2010. In it I told him that if he were still hosting that show in Brooklyn, I’d love to do another set. Obviously, he never responded. But for months I thought I must have done a shittier job than I’d previously thought. Either that, or Abe was a dick. (Fuck him and his hipster audience!)

I think about tidying up my Facebook page. Should I leave this world, before my next status update, I’d want to leave behind a good-looking wall: good links, clever comments, and enough photos so people know that I—like the countless friended—had a life not spent entirely on Facebook.

But should I die and I am unable to update my status, I wonder how others will find out about it—particularly the people who encountered me only briefly. What sort of fabrication of Lou will they cobble together?

Lou is ___________.

Lou is a ___________.

Lou is an ___________.

*

I don’t wait for Deepak to respond to the message I sent him. I go ahead and send a message to one of the family members from Abe’s Red Sox pic. (He’s on Facebook too. He’s left comments on Abe’s wall.) He writes back to me shortly thereafter, thanks me for reaching out.

Abe died in October of 2009—four months after I did my stand-up set at his show, and nine months before I ever thought his death possible.

Abe was 24-years-old. I’m sorry I never knew him. This is my proof.

[…] many rejection letters, Lou’s essay, “This Is My Proof,” has finally found a home—at Zouch […]