The Art and Literature of Japan’s Emoji Phenomenon

Culture, DigitalIf you’re not in the mood to know the news of the day, do pay a visit to the “Icons Times.” It’s a “newspaper” in the form of, well, colorful icons. You’ll find, in its archives, an image of a sexy, stiletto-heeled pump, with a knife point, sticking out of the welt of the shoe.

Icons Times Shoe

The accompanying headline, taken from The New York Times, reads: “First Woman is Chosen to Lead the Secret Service.” James Bond buffs will instantly recognize the inspiration for it. It comes from a character in “From Russia with Love” (1963): Colonel Rosa Klebb, a high-ranking member of the feared Russian counter-intelligence agency, SMERSH, who wears a flat-leather moccasin that carries a retractable knife. To the rest, it probably will mean not a smidgen more than that which is obvious.

Pictorial depiction of media stories has no future.

Pictorial communication, however, using emoji, is another story altogether. If you’re not a digerati, or are below a certain age, or not an iPhone owner, you’re not likely to have even heard the word—but, it’s a fast evolving into a lingua franca of the Millennials. A peanut-size ideogram, an emoji is tech-version of a pictogram, made up of codes, which serves as a proxy for an emotion, a gesture, or an object (both animate and inanimate). It’s easy to confuse them with “emoticons,” which are far less complex, used only to convey a mood, and created simply using punctuation marks, numbers, and letters.

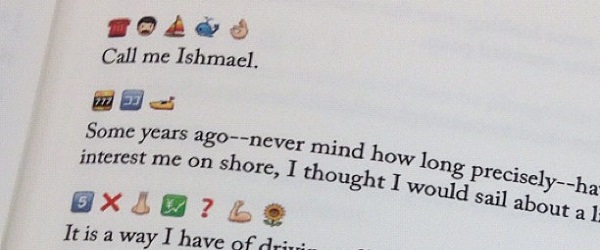

Oh, wait, the language, though only in its infancy, has already produced a masterpiece. Fred Benenson’s “Emoji Dick” is an epic translation of Herman Melville’s 200,000-word classic, “Moby Dick” into emoji. Not to be frowned upon, it’s now, been inducted into the Library of Congress’ catalog. A crowdsourced and Kickstarter-funded project, it was the work of a battalion of 800 Amazon Mechanical Turks.

Fred Benenson’s Emoji Dick

Emoji is as Japanese as sushi, ramen, or Toyota. Around the end of the 20th century, in Japan, e-mail exchanges were gaining momentum and the pager rage was picking up. One of the pitfalls of a faceless connection was that it was seldom easy to gauge the tone of a message. When a sender shot off a note, was he or she intending to be flippant, flirty, ferocious, fiery, or finicky? The emoji supplied what was missing from it—feelings, tone of voice, body language. They made chats and texts sentient.

There are as many emoji today, as there are squares in a box of Chex cereal. There’re visages, frozen in myriads of expressions to creatures from the animal kingdom to flora to machines to food to faces of clocks to zodiac signs to weather phenomena: panda, rooster, penguin, hibiscus, megaphone, hour-glass, fax, kimono, lipstick, sushi, hamburger, donut, ramen, barber, trolleybus, toilet, tent, house, astonished to pensive, alien.

If stylish typography can be art, then, surely, emoji, which are, after all, small pictures, can be the building blocks of bigger pictures. So is to the logic propelling this newest of art forms. As part of its annual contest, earlier this year, when The New Yorker sought reader submissions for its anniversary issue cover design, featuring its mascot, the dandy, Eustace Tilley, Benenson decided to send one, painted in with his medium. Born was a winner: “Mr. Eustace Emoji.”

Fred Benenson’s Emoji cover of The New Yorker

To bestow legitimacy to the fad, if it’s that, Forced Meme Productions, a Brooklyn-based creative collective, is hosting the first-ever emoji art exhibition, which will run at the New York City Eyebeam Art and Technology Center from December 12th to 14th.