Flipping Tibor Fischer

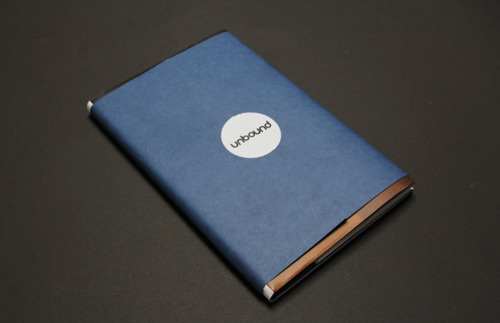

Books, ReviewsThe end papers of Tibor Fischer’s new book take design inspiration from Greek pottery and the London Underground. The former prefixes a story about the Trojan War, the latter a woman who returns to her London flat to find the locks are changed. The reader can choose which story to read first and then ‘flips’ the volume over to read the next one. As an artefact the book did feel as though I was handling a piece of priceless Grecian Pottery. It arrived bound in dark blue paper, the dust jacket photography is by acclaimed Czech photographer Hana Vojakova, the individual covers are beautiful, there’s a note on the book’s typeface and the endpapers are highly stylised and, according to the press release, finished with a subtle grey wash. Let’s see you do all of THAT on a Kindle. There’s no denying that as an object it’s certainly well considered but are the stories any good?

I read Possibly Forty Ships three times. The first attempt I had one eye on Eastenders and had no idea what was going on (in both the book and Albert Square) but by the third reading I think I had it sussed. A man is being interrogated with the threat of torture to recount his experience and involvement in the Trojan War, that staple of Homer’s Epics. It’s a brief retelling of the myth with a few gags thrown in: ‘Once you’ve had your wife in fifty-six positions, it’s not the same’. Poor Achilles is a trannie, no doubt his thigh high platforms the cause of his infamous podiatry problems; he ends up in the King of Ethiopia’s bed where he’s ‘bummed into madness’ to the extent that ‘you could drop a vole into his rear.’

The writing’s pretty clever: before being written down, Homeric myths were transmitted orally, probably like Achilles’ STIs, and the story is all dialogue. The man being interrogated uses a Homeric technique of repetition (an ancient rhetoric device that helped in the memorising of tales): ‘the truth? How do you define – ‘, ‘How do you define war? What is a – ‘, ‘How would you define a hero?’

Tibor’s style and the themes of failed marriages, sex and un-heroic heroes wouldn’t be out of place in a contemporary celebrity magazine, thus showing that stories in their general sense are timeless, the tales might be different but the human involvement is always recognisable. Likewise, war stories, possibly more so in our own times, are always distorted. The man questions his interrogator’s presumptions, claiming that a fleet was actually just a few ships (possibly forty), that not all the soldiers were heroes, some were blind and had chronic back pain. ‘It’s a pity pleasure can’t, like a stream, flow endlessly out of one person. There would be fewer burning cities.’ Read that in respect to a disgruntled Commander in Chief and the pursuit of war is all down to a lack of leisure time. Anhedonia is a warmonger.

In the centre of the book is a list of names of people who funded the book’s creation. The publisher Unbound, puts book proposals out to tender and potential readers who would like to see the thing written can pledge funds towards print costs etc. It’s part Victorian philanthropy part democratisation of the creative process. Democratisation might be going a little too far, especially if you’re skint and can’t afford to make a donation; but it’s a very clever way of shifting the risk of publishing a book away from the publisher onto the readers.

It’s a good idea though: everyone likes to see their name in print, even vicariously in another author’s book. Unbound intends to open the opportunity to first time writers but for now it’s just published authors, including Kate Mosse and Vitali Vitaliev, or proposals submitted by literary agents. I hope they follow through the intention of giving first-timers a chance, if not, just giving published authors another platform to further their work rests a little uneasily for me.

*Flips the book over*

From Greek myth to modern urban alienation (or vice versa), Crushed Mexican Spiders tells how a woman’s life is basically paused and dissolved when she realises the locks on her front door have been changed. This device works on a couple of levels. Firstly, it’s written like the opening of a longer book, creating intrigue that could go on to be resolved. Secondly, like the beginning of Forty Ships, it’s cinematic, focusing the narrative onto the woman’s incomprehension at what is happening to her. Thirdly, I related to the woman’s growing terror at discovering that everything she knew when she woke up that morning, her life, has either been dissolved or was simply a fiction of her own mind.

Take a minute to imagine this: you come home to find your key doesn’t work, you buzz your flat and a woman answers who claims to have lived there for years, your neighbours don’t recognise you either. You go to a phone box and call your friends but the numbers ring out or aren’t in service. You finally call the police, hoping they’ll make sense of everything, but when they ask if you have proof of address you’ve lost the utility bill in your bag and the woman who now lives there can use her own paperwork to prove she really is the occupier. Your final desperate attempt at proof is telling the officer the colour of your bedroom curtains, only to be proved wrong.

The story could happily be an amnesiac themed episode of Holby City, but that’s no bad thing. Mexican Spiders is disorientating and unnerving in a way that some longer stories, TV shows and novels could only hope to be. To get all subjective and reader response for a second, I found the dead body of a neighbour in their home a couple of weeks ago and the story reminded me of it: I got up that morning thinking it would just be a day like any other, only to find myself identifying a part-decomposed cadaver. The woman in Mexican Spiders must have felt something similar. Life changes in an instant, in her case with the turn of a key.